The American Slavery Collection, 1820–1922 from the American Antiquarian Society

This digital edition of the American Antiquarian Society’s extraordinary holdings of slavery and abolition materials delivers more than 3,600 works published over the course of more than 100 years. Materials include books, pamphlets, graphic materials, and ephemera on topics that include the Missouri Compromise and the founding of Liberia; the first National Anti-Slavery Society Convention in 1837 and the Compromise of 1850; the Emancipation Proclamation and the establishment of “Redeemer” state governments; the birth of “Jim Crow” and the expansion of segregation through the early 1920s. For more information, contact Lawrence Busenbark, Metadata Specialist / Bibliographer.

Women and Social Movements International

This resource of primary source material focusing on women’s international activism since the mid-nineteenth century includes proceedings of women’s international conferences, books, pamphlets, articles from newspapers and journals, as well as diary entries. The United Nations Commission on the Status of Women, Anna Lord Strauss Papers, and the Inter-American Commission on Women’s Records are some of the materials you will find. For more information, contact Leslie Homzie, Sr. Research Librarian for Communication, Sociology, Women’s and Gender Studies

Thesaurus Linguae Latinae

The Thesaurus Linguae Latinae is a comprehensive Latin to Latin dictionary based on all available Latin texts (including inscriptions and other non-literary material) for the period up to 600 AD. Its primary uses are etymology and exhaustive examples of usage. Continuously published and updated in Germany since 1894. For more information, contact Chris Strauber, Sr. Research Librarian for Theology and Philosophy.

Economist Digital Archive

The Gale Cengage Economist Historical Archive provides researchers searchable online access to The Economist back to 1843. This important resource covers international news with a focus on finance, politics and business. It also includes current science and technology insight. For more information contact Barbara Mento, Economics Librarian.

Chinese Newspapers Collection

Full-text access to 22 English-language Chinese historical newspapers published between 1832 and 1953. Topics include the end of imperial rule in China, the Taiping Rebellion, the Opium Wars with Great Britain, the Boxer Rebellion and 1911 Revolution, and the subsequent founding of the Republic of China. The full-image newspapers provide searchable access to articles, advertisements, editorials, cartoons, and classified ads. For more information, contact Kimberly Kowal, Interim Liaison Librarian for History.

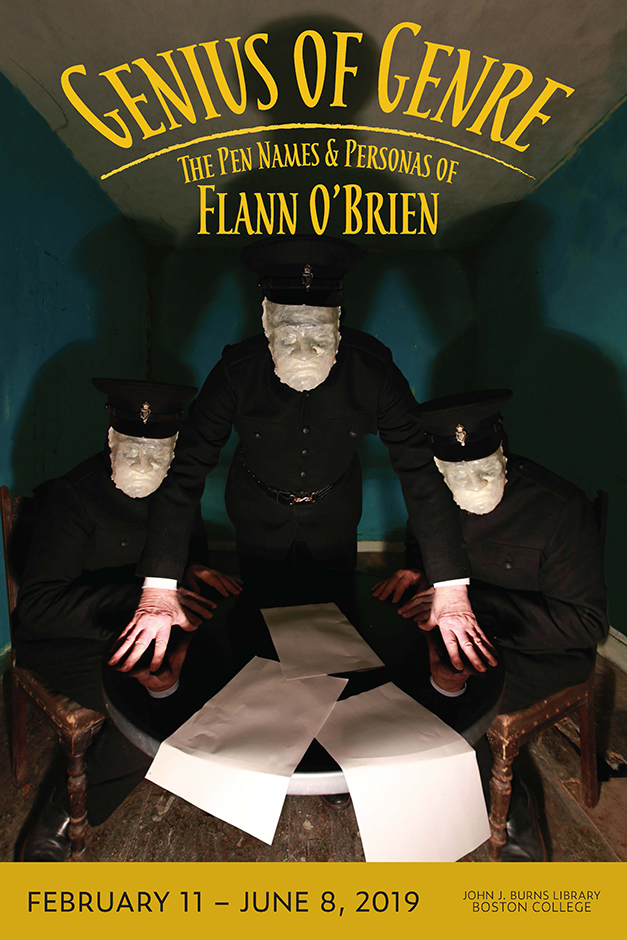

Flann the novelist. Myles the columnist. Brother Barnabas the student. Brian O’Nolan (1911-1966) wrote in many genres under many guises, in both English and Irish, confounding contemporaries with his incomparable genius and satirical wit.

Flann the novelist. Myles the columnist. Brother Barnabas the student. Brian O’Nolan (1911-1966) wrote in many genres under many guises, in both English and Irish, confounding contemporaries with his incomparable genius and satirical wit.

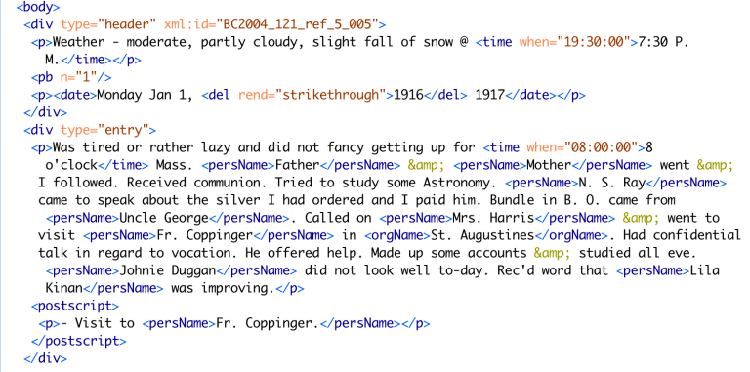

One hundred years after it was penned, a single diary from the

One hundred years after it was penned, a single diary from the