DLEM themes

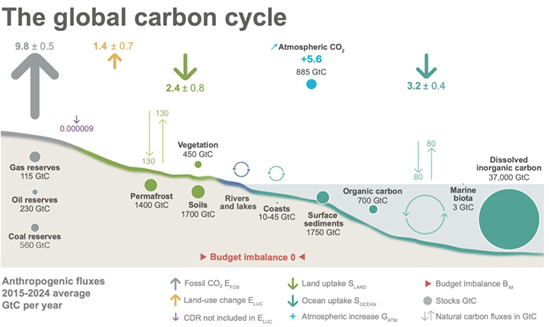

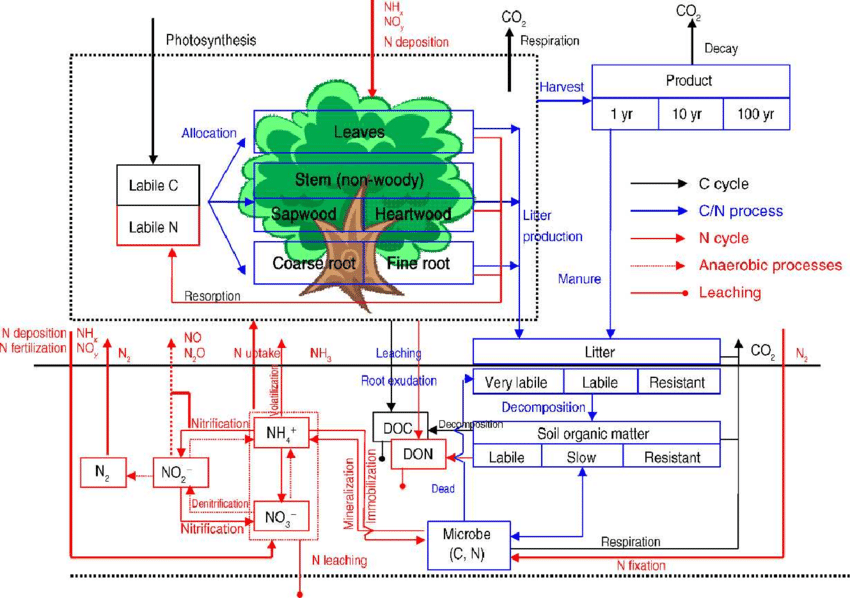

The exchanges of carbon dioxide (CO2) between terrestrial ecosystems and the atmosphere in the DLEM framework are governed by the balance between photosynthetic carbon uptake and multiple respiratory carbon loss processes. These include autotrophic respiration from plant tissues and heterotrophic respiration associated with microbial decomposition of soil organic matter. Together, these processes determine net ecosystem productivity (NEP) and the land carbon sink.

Photosynthesis in DLEM is represented using a biochemical formulation based on the Farquhar model for C3 plants and the Collatz-type formulation for C4 plants. Carbon assimilation is influenced by key environmental drivers such as solar radiation, air temperature, atmospheric CO2 concentration, soil moisture, and plant nitrogen status. Dynamic allocation schemes distribute assimilated carbon among leaves, stems, roots, and reproductive tissues according to plant functional type and phenological stage.

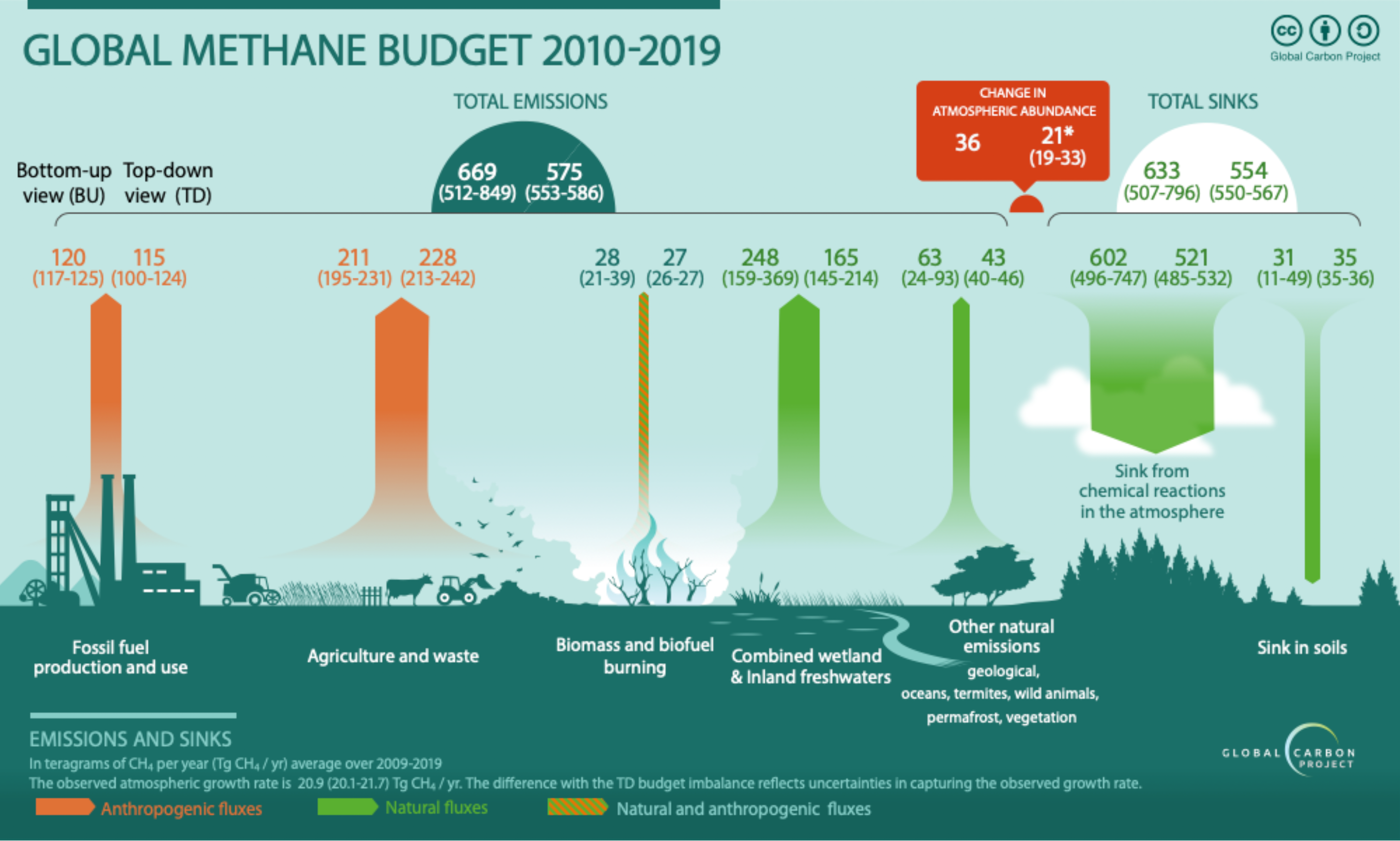

The exchanges of methane (CH4) between terrestrial ecosystems and the atmosphere result from the combined effects of CH4 production, oxidation, and transport from soil pore water to the atmosphere (Tian et al., 2010; Xu et al., 2010). In the DLEM framework, CH₄ production is derived solely from dissolved organic carbon (DOC), which is indirectly regulated by key environmental factors including soil pH, temperature, and soil moisture. CH4 oxidation including oxidation during vertical transport, oxidation within soil pore water, and atmospheric CH4 oxidation at the soil surface is controlled by CH4 concentrations in the air or soil pore water, as well as soil moisture, pH, and temperature. Most CH4-related biogeochemical reactions in DLEM follow the Michaelis–Menten formulation, characterized by two key parameters: the maximum reaction rate and the half-saturation constant.

Three pathways are considered for CH4 transport from soil to the atmosphere: (1) ebullition, (2) molecular diffusion, and (3) plant-mediated transport. DLEM assumes that CH4 related biogeochemical processes occur primarily within the upper 50 cm of the soil profile.

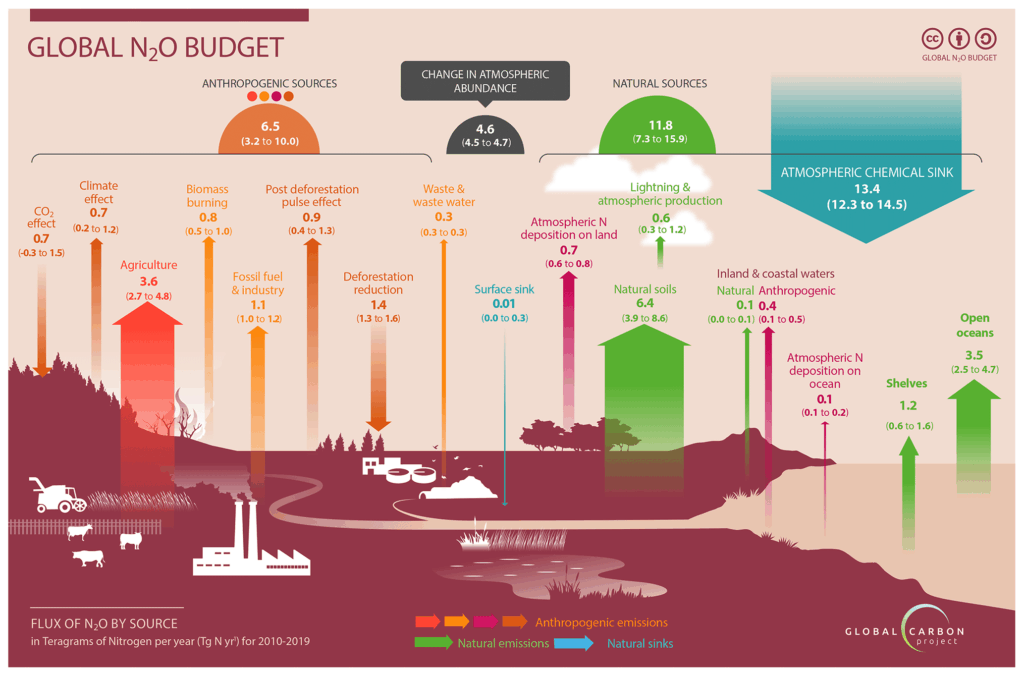

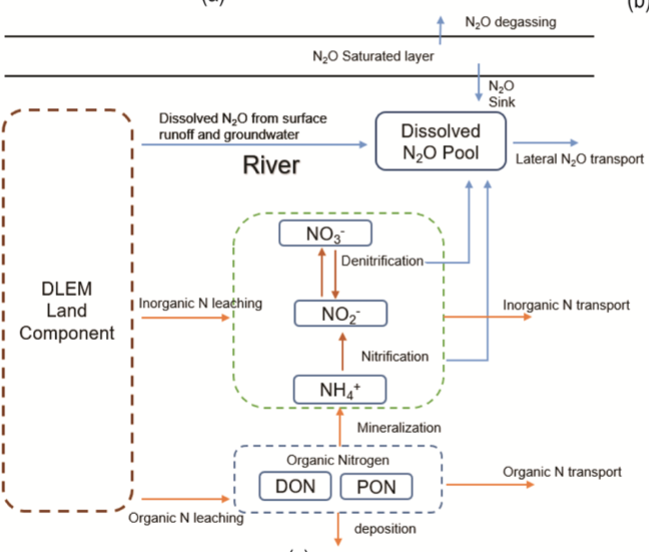

Nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions in the DLEM framework are generated mainly through two microbial pathways: nitrification and denitrification (Tian et al., 2012). The model simulates both processes by accounting for nitrogen availability, soil temperature, water-filled pore space, and other soil physical and biogeochemical properties.

Nitrification converts ammonium into nitrate and is modeled as a function of soil temperature, soil moisture, and the amount of available ammonium in the soil. The model determines the daily fraction of ammonium transformed, regulated by temperature and moisture response functions (Yang et al., 2015).

Denitrification, which reduces nitrate into nitric oxide, N2O, and dinitrogen, is simulated using potential denitrification capacity, soil clay content, heterotrophic respiration, plant functional-type parameters, soil temperature, soil moisture, and soil nitrate concentration. Soil bulk density is used to convert nitrate concentrations into area-based quantities.

The portion of assimilated carbon remaining after growth respiration is allocated among plant tissues according to resource limitations and phenology. DLEM uses a relative allocation strategy following Friedlingstein et al. (1999), in which allocation priorities reflect the most limiting resource. Resource constraints are grouped into above- and below-ground types: when above-ground resources such as light are limiting, more carbon is directed to stem (sapwood) growth to improve light capture, whereas limitations in below-ground resources shift allocation toward roots to enhance water and nutrient uptake. Because water and nitrogen are both below-ground constraints, the model assumes only the most limiting of the two controls root allocation, giving equal weight to above-ground (light) versus below-ground (water or nitrogen) limitations. Thus, stem allocation is regulated by light stress, while root allocation is driven by whichever below-ground resource is scarcest, determining how available carbon is partitioned among tissues.

Daily biological nitrogen fixation is derived from the annual fixation amount scaled by atmospheric CO2 concentration, and the resulting fixed nitrogen is added directly to the soil ammonium pool. Nitrogen deposition is supplied as annual ammonium and nitrate inputs, which the model distributes into daily values according to each day’s share of annual precipitation, with a smaller fraction evenly spread across all days; these deposited amounts are added to the soil inorganic nitrogen pools. Plant nitrogen uptake depends on maximum uptake capacity, soil temperature, and the combined effect of soil moisture and available inorganic nitrogen. Actual uptake is limited by potential uptake, the available soil ammonium and nitrate, and the plant’s nitrogen deficit relative to minimum tissue C:N ratios. After uptake, the soil nitrogen pools are reduced proportionally.

Total nitrogen available for plant allocation includes both stored nitrogen and newly absorbed nitrogen, which is redistributed among tissues according to their minimum C:N requirements. Leaf nitrogen is further partitioned between sunlit and shaded leaves using a nitrogen extinction factor, resulting in higher nitrogen concentration and lower C:N ratio in sunlit leaves compared to shaded leaves.

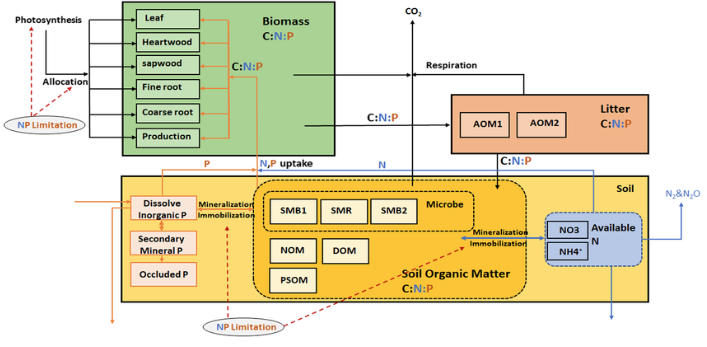

We incorporated the P processes into the DLEM-CN, and the cycles of C, N, and P are fully coupled in the major processes including photosynthesis, allocation, turnover, nutrient uptake, and decomposition in the newly developed DLEM-CNP. In the DLEM-CNP, organic P transfers into inorganic forms through mineralization in the soil, while inorganic P converts to organic form through immobilization and vegetation uptake.

Structure of C-N-P cycles in DLEM-CNP:C enters the ecosystems through vegetation CO2 uptake during photosynthesis. The plant biomass box consists of six C, N, P pools: (leaf, heartwood, sapwood, fine root, coarse root, and production). Litters are grouped into two added organic matter pools (AOM1 and AOM2) with different residence time. Soil organic matter has six pools: three microbial pools, namely, soil microbial 1(SMB1), soil microbial 2 (SMB2), and soil microbial residues (SMR), and three slow soil organic matter pools, namely, native organic matter (NOM), passive soil organic matter (PSOM), one dissolved organic matter (DOM)

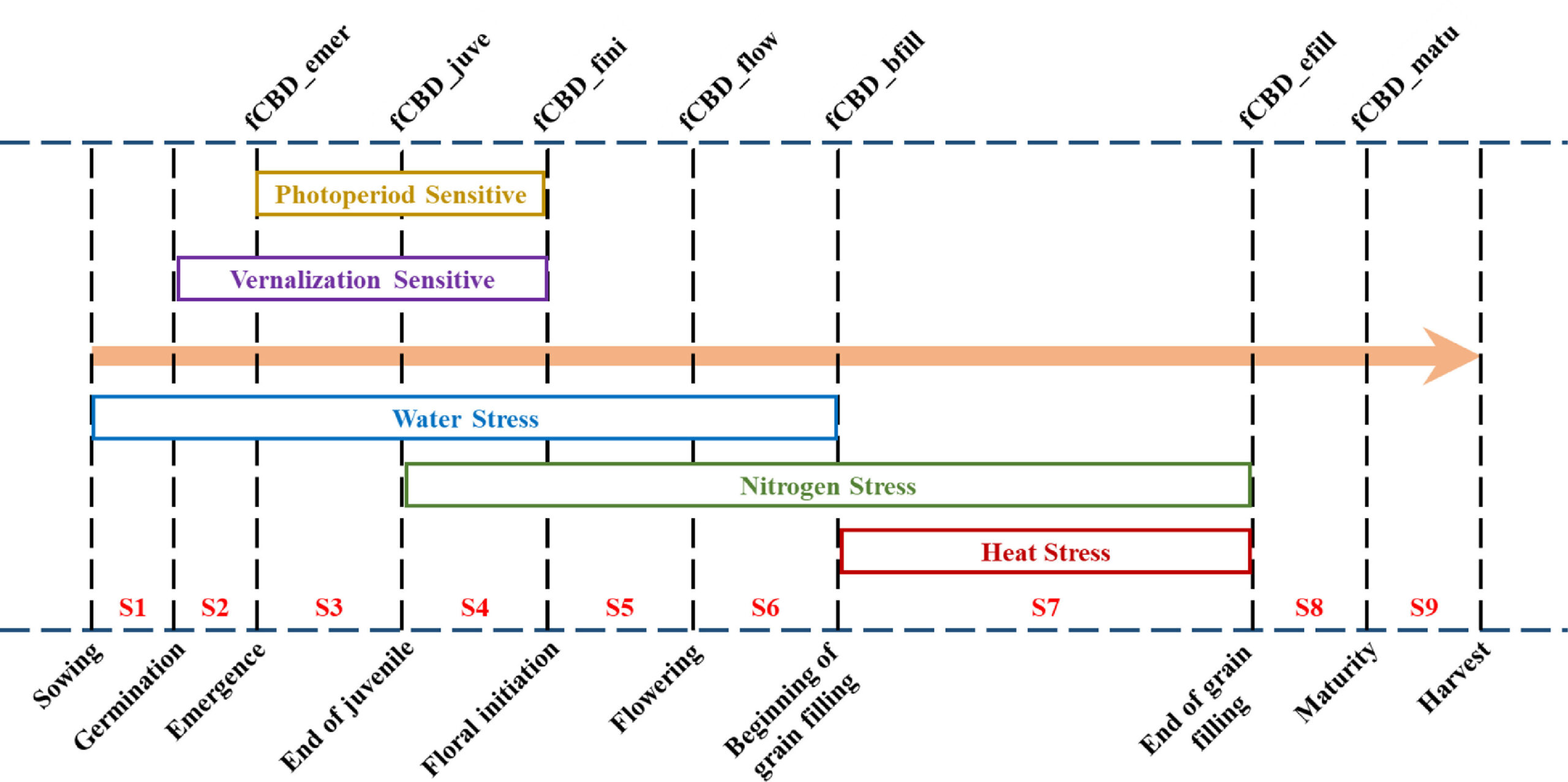

The new agricultural module is developed based on previous agricultural versions of DLEM (DLEM-Ag and DLEM-Ag2), which included simplified crop growth processes and basic management practices (e.g., nitrogen fertilization, irrigation, and crop rotation). The updated module incorporates expanded process representations, enhanced management options, and improved coupling with biogeochemical and hydrological cycles.

See our paper by You et al. →

The dynamic vegetation component in DLEM simulates two kinds of processes: the biogeographical redistribution when climate changes, and the plant competition and succession during vegetation recovery after disturbances. Like most DGVMs (Dynamic Global Vegetation Models), DLEM builds on the concept of PFT (Plant Functional Type) to describe vegetation distributions.

Wetlands are defined as those areas that are inundated or saturated by surface water at a frequency and duration sufficient to support vegetation growth, which leads to five wetland types: (i) rice paddy, (ii) permanent herbaceous wetland, (iii) permanent woody wetland, (iv) seasonal herbaceous wetland and (v) seasonal woody wetland. DLEM simulates water transport to rivers based upon catchments, but does not explicitly move water through grid cells and thereby does not influence conditions in neighbouring grid cells.

DLEM represents grassland productivity and loss processes under changing climate and varying herbivory intensity, explicitly accounting for how increasing animal populations influence above- and below-ground biogeochemical cycles. Herbivory alters grassland functioning through several mechanisms: it reduces leaf biomass and light interception, modifies canopy structure, and lowers transpiration, thereby influencing water stress; it accelerates nutrient cycling and enhances nitrogen availability; it shifts plant allocation strategies by altering carbohydrate and reserve distribution; and it can directly damage vegetation through grazing and trampling or indirectly suppress growth through soil compaction. Together, these processes determine how grazed grasslands respond to environmental and ecological change.

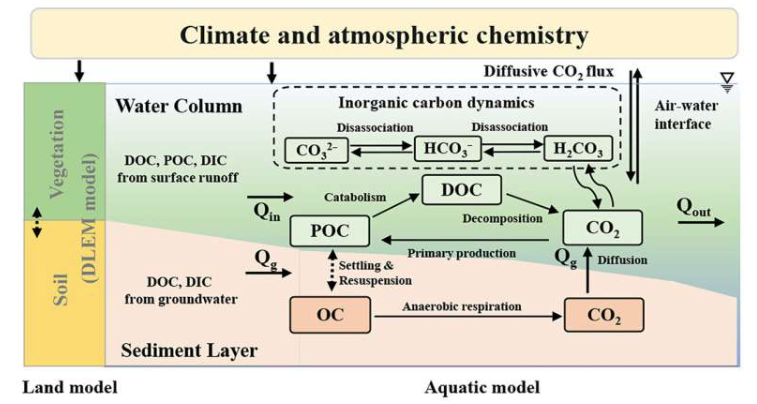

The DLEM riverine model calculates river routing and the biogeochemical processes in aquatic ecosystems. The mineralization of dissolved organic nitrogen to NH4+ is mainly controlled by water temperature, while NH4+ nitrification and NO3− denitrification are primarily regulated by water temperature and flow velocity. We improved the DLEM aquatic model by adopting a scale-adaptive river routing scheme, allowing us to quantify physical and biogeochemical processes in small streams—systems that are usually overlooked in most regional and global modeling studies. In addition, a riverine N2O model was developed to simulate N2O emissions from river channels.

In DLEM-TAC, water transport within each grid cell is represented through three sub-grid processes: hillslope routing, subnetwork routing, and main channel routing. A scale-adaptive and physically based hydrological framework—Model of Scale-Adaptive River Transport—is incorporated into DLEM to simulate these processes. Surface runoff water is first routed through hillslopes. Water arriving in subnetwork channels from hillslope flow and groundwater discharge is then conveyed into the main channel. Note that the subnetwork channels within a 30 arc-min grid cell represent stream orders 1–5. The main channel receives water from upstream grid cells and local subnetworks, and then discharges it to the downstream grid cell. All three routing processes use kinematic wave methods and require several physical parameters—channel length, bank-full depth, channel slope, and channel roughness—derived from a 15 arc-second global hydrological dataset.

We estimate global livestock CH4 emissions from 1890 to 2019, following the new IPCC (2019) guidelines. A total of 10 categories of livestock—including dairy cattle, nondairy cattle, buffaloes, sheep, goats, pigs, camels, horses, mules, and donkeys—were assessed. We established long-term population sequences at the national scale and developed high-resolution gridded CH4 emission maps at 0.083° (~9 km). This study aims to evaluate long-term trends and spatial patterns of livestock CH4 emissions from local to global scales over the past 130 years.

DLEM simulates four general land-use change categories, i.e. land conversion from natural vegetation to cropland, land conversion among different natural vegetation types (if parameters are available), cropland abandonment, and urbanization. During land conversions, partial vegetation carbon is removed as product pools, partial vegetation and soil carbon is released to the atmosphere through land conversion flux, and the rest enters the litter carbon pool. Three kinds of product pools are defined in DLEM: 1- (PROD1), 10- (PROD10), and 100- (PROD100) year product pools, which represent 1-, 10- and 100-year turnover time. The rest of the vegetation biomass enters different aboveground or belowground litter carbon pools. Accompanying carbon redistribution after land-use change, the ecosystem nitrogen and hydrological cycles are correspondingly changed.

The DLEM-Fire is a process-based fire module built within DLEM. It is capable of estimating burned area, fire emissions, and fire impacts on ecosystem function and structure by simulating fuel characteristics, number of fires, and fire behavior. Since this study aims to reconstruct the historical burned area, we focus on the algorithm for estimating burned area rather than fire emissions and fire impacts.

See our paper by Yang et al. →

The portion of assimilated carbon remaining after growth respiration is allocated among plant tissues according to resource limitations and phenology. DLEM uses a relative allocation strategy following Friedlingstein et al. (1999), in which allocation priorities reflect the most limiting resource. Resource constraints are grouped into above- and below-ground types: when above-ground resources such as light are limiting, more carbon is directed to stem (sapwood) growth to improve light capture, whereas limitations in below-ground resources shift allocation toward roots to enhance water and nutrient uptake. Because water and nitrogen are both below-ground constraints, the model assumes only the most limiting of the two controls root allocation, giving equal weight to above-ground (light) versus below-ground (water or nitrogen) limitations. Thus, stem allocation is regulated by light stress, while root allocation is driven by whichever below-ground resource is scarcest, determining how available carbon is partitioned among tissues.

The DLEM is a fully distributed, process-based land surface model that integrates major terrestrial hydrological processes, plant physiology, soil biogeochemistry, and riverine routing dynamics. It explicitly simulates carbon, nitrogen, and water fluxes among vegetation, soils, and the atmosphere in response to atmospheric CO2, climate variability, nitrogen deposition, land-use and land-cover changes, fertilizer applications, irrigation, and other management practices. Surface runoff, subsurface drainage, and nitrogen exports generated by DLEM—including nitrate (NO3−), ammonium (NH4+), and dissolved organic nitrogen—serve as inputs to the riverine biogeochemical module.

The DLEM riverine model simulates hydrological routing and nitrogen cycling processes within aquatic ecosystems. Mineralization of dissolved organic nitrogen to ammonium is primarily regulated by water temperature, while ammonium nitrification and nitrate denitrification depend jointly on water temperature and flow velocity.

In DLEM, the basic simulation unit for herbivore population dynamics is the grid cell, within which up to four herbivore types may coexist. Although this study focuses on simulating the population dynamics of four representative herbivores at the site level, the model structure is designed to be fully scalable and applicable to any herbivore group at regional to global extents. We simulated cattle, horses, sheep, and goats across Mongolia, Africa, and the United States to evaluate differences in grazing versus browsing strategies.

We distinguish grazers from browsers such as goats based on established behavioral and dietary patterns. Grazers primarily consume surface-level herbaceous biomass, whereas browsers preferentially feed on intact foliage, buds, and woody stems (Askins & Turner, 1972). Goats are treated as mixed feeders that rely on highly digestible plant components, including buds, leaves, fruits, and flowers that are rich in protein and low in fiber. Under limited availability of these preferred tissues, goats gradually shift their diet toward grasses.