“A Dream for the Academy” is my talk delivered as the outgoing president at the Academy of Management Meeting in August 2002. I served as the President of the Academy of Management from 2001-2002. The full talk and power point slides are below, as well as available for download to the right.

Download full presentation and speech here:

A Dream for the Academy

Jean M. Bartunek

Presidential Address

Academy of Management Meeting, Denver, CO

August 13, 2002

In December of 1997 Mike Hitt, who was then past president of the Academy of Management and thus in charge of the nominations process for positions on the Board of Governors, called me to tell me I’d been nominated for President of the Academy and inviting me to run for the position. I told him I’d make a decision about whether or not to accept the nomination the same way I make most serious decisions. That is, I’d have a dream about it and work with the dream, and, depending how the work with the dream came out, either accept the nomination or not.

I realize that working with dreams probably isn’t the primary way many of us in the Academy make decisions. However, this approach had worked effectively for me in the past, so it seemed worth trying

Sure enough, a couple nights later I dreamed that I went shopping for shoes with Deborah Ancona, who is a professor of Management at the Sloan school of Management at MIT.

The shoe store we were going to was up on the roof of a tall apartment building. And this apartment building, in turn,

was next to an even larger warehouse that was owned by the parents of some of my students.

I was sure this shoe store wouldn’t have shoes that were my size. Somewhat to my surprise, however, the store did have some shoes that were my size, though some of them were ugly.

I worked with the dream the next morning, and it soon became evident that there was a metaphor in it, “the shoe fit,” even if it might be a little ugly. This was enough for me to decide to accept the nomination, and here I am a few years later to tell the tale.

But it seemed to me that there was more to the dream than that one metaphor. So over the next few months I consulted with some people who are very familiar with symbolism in dreams. I was looking for imagery that might be informative not only about the yes/no decision regarding whether to run for president of the Academy, but about some of the experience I might be having, and, perhaps, we might be having jointly as Academy members. After all, the executive committee of the Academy, from professional development workshop chair through past president, is a five year journey. It is traveled to some extent with all academy members, and shoes are an integral part of a journey.

In doing this further exploration, I became aware of three symbolic images embedded in the dream. These have to do with the warehouse, the fact that the shoe store was on top of an apartment building, and the dual facts that the warehouse was owned by parents of my students and that I was shoe shopping with Deborah Ancona. Deborah and her husband have four children, all of whom, at the time of the dream, were under seven years old.

I have tried to pay attention to each of these symbolic images in conjunction with various Academy events I’ve experienced over the course of the past few years, and I’m going to talk about each of them this afternoon. When I talk about them, I’ll be using them as lenses to reflect on my experience and our experience as an Academy, not only internally, but also in relation to the world we are finding ourselves in this year.

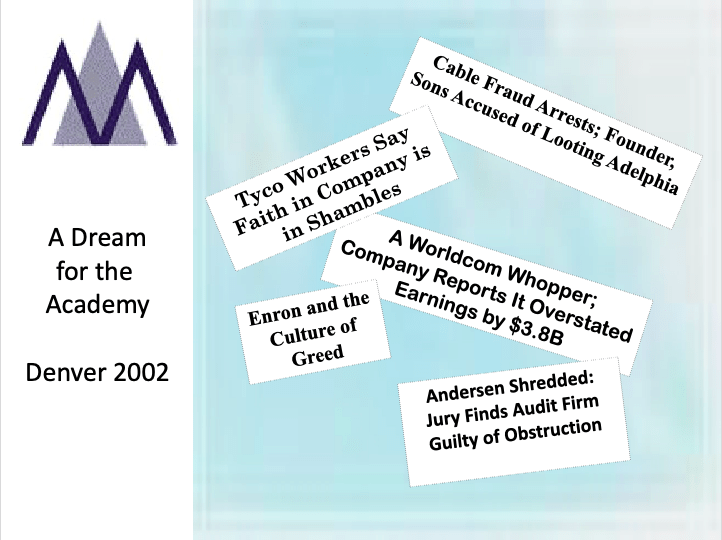

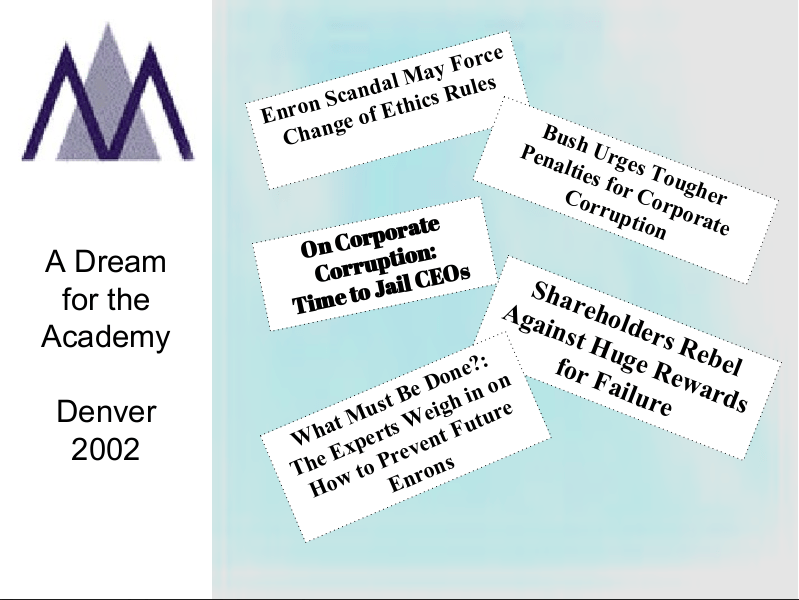

Academy presidents have sometimes wondered what, if anything, we had to say to our larger world. This year, this summer particularly, when there is one of the worst crises in corporate management ever seen, when subjects that have sometimes seemed to be of limited interest to people outside major corporations, such as executive stock options, the composition of corporate boards, CEO-chairman duality, corporate ethics, reports of revenues — have become daily fare on the evening news and in newspapers around the globe, it is absolutely crucial that we have something to say.

Some of the Academy experiences I’m going to describe based on my dream might at first seem quite separate from the corporate scandals we are witnessing. However, I believe these Academy experiences, illuminated by the symbols in the dream, might stimulate our imagination in ways that can help us make important contributions to these significant corporate issues and other ones as well. That is my hope and intent for this presentation.

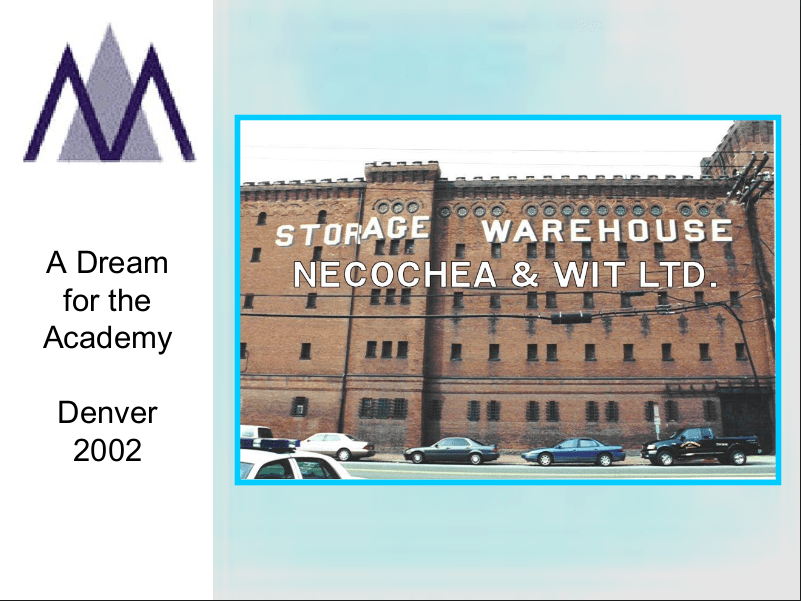

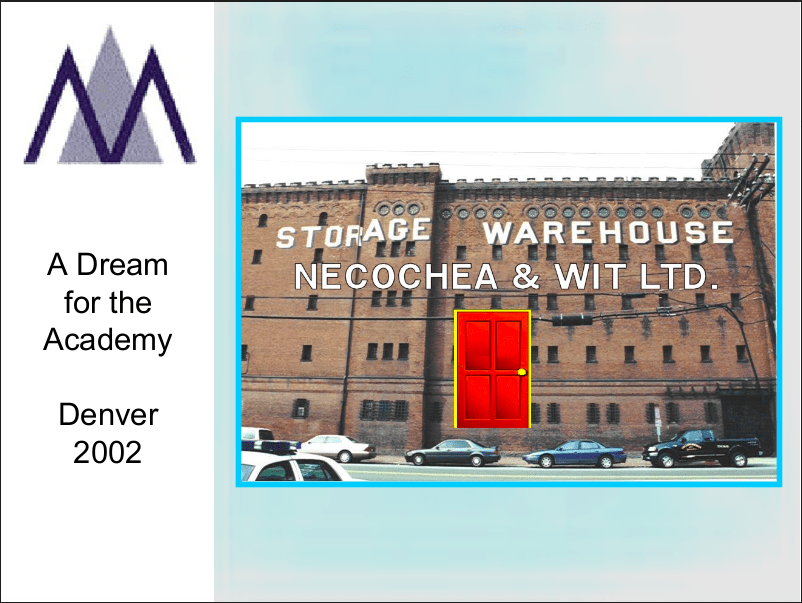

The Warehouse

Let’s start with the very large warehouse. I’ve learned that in dreams a warehouse symbolizes both having resources available and putting things away in storage. Some of what we store we don’t have much use for any more, but many things in storage have to be available for efficient access at the right time.

The first meaning, having resources available, especially intellectual and creative resources, is certainly a central feature of the Academy. There have been incredible resources available to me personally and to the Academy as a whole, and I want to name just a few.

I am very grateful to Raul Necochea, Mirjam Wit, and Frank Klemovitch, who have been my primary assistants on Academy activities throughout these four years.

There have been many other people at Boston College who are making this journey possible by providing help when I or others need it.

The entire Academy Headquarters staff is exceptionally helpful, to me and to others in almost any conceivable type of situation.

The program chairs during the year I chaired the annual meeting, many of whom are division chairs this year, did wonders, and that’s true of other groups of program chairs as well.

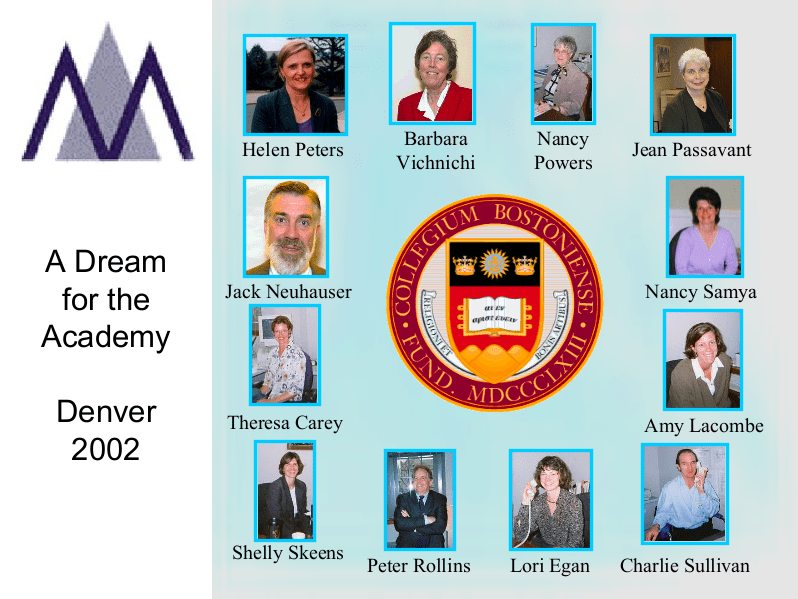

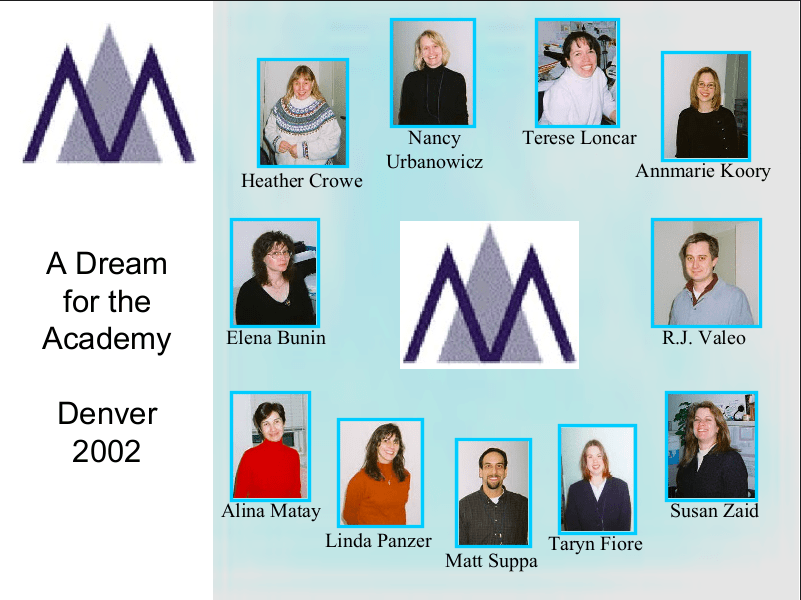

The Board of Governors you see sitting here works very hard, and the Academy has many committed and dedicated volunteers, especially the various committees and task forces and their chairs, and so I’m showing, as I did at the convocation, two slides of committee chairs to symbolize all volunteers in the Academy. In fact, if I recall correctly, when our executive director Nancy Urbanowicz did a count of people volunteering for one or more Academy activities she found several thousand people. If you just look at the lists of reviewers in this year’s Academy meeting program you will find thousands of people, and many others volunteer in other important ways at the meeting and well beyond it.

Not only do we have resources, but the Academy depends on them totally. The help so many members provide is one of the things that makes the Academy, to my mind, at least, a wonderful association.

This can seem like a totally internal issue in the Academy. But it can also be a model for stimulating new ways of thinking about the use of resources.

Not all, but many scholarly approaches to resources focus on them as something to hoard, to use as a power base, to make others dependent on us. Taken too far, this is one of many indicators of greed, something we’ve seen illustrated over and over this summer. Sometimes the resources don’t even exist, but are invented whole cloth.

But as I’ve just illustrated, we have examples in the Academy and elsewhere of people who generously make resources available to others in ways that go well beyond exchange agreements. These kinds of actions can provide a source for imagining and studying conditions under which top managers and their organizations can use their resources in ways that are more creative, helpful, and productive for themselves and others.

But what about the second meaning of the warehouse, the resources we put in storage and that may or may not be easily accessible? What do we as Academy members put in storage, and how much of what we’ve got there is accessible for active use in a timely manner?

For each of us, some of what is produced in the Academy is relegated to the warehouse bins; we have so many resources that we often don’t know how to use them all. Our annual meetings, for example, are stimulating and wonderful and often overpowering; we can’t take it all in. Our journals often include more information than we can use at any given time. We have many talented and gifted members. We are very lucky.

But other people need our resources, and so it’s more important to focus on whether, and how, the Academy and our stakeholders can get access in a timely fashion to them. This is a much more complicated issue.

I’ve been aware during the past few years, for example, that there are members whose skills I wish I’d known about, but didn’t, and members who don’t feel welcome at Academy events, but whose contributions could help substantially. One challenge we have is the ability to better find and access the contributions of all of the Academy members who are interested in and willing to make a productive and constructive contribution to the Academy’s work, wherever they reside and whatever their affiliation.

I’m particularly concerned about the difficulties we have in making our work accessible to our stakeholders outside the Academy. Sometimes it feels to our stakeholders as if our warehouse door is shut tight,

or that even if they can find a way in, it’s difficult to make sense of and be able to use the resources we have.

But a time of corporate crisis is a crucial time for what we do to be accessible, in multiple meanings of that term, including possible to find and then possible to understand. I believe that, in particular, we have the scholarly resources, with the term scholarship considered broadly, to be helpful to societal stakeholders concerned about this crisis – not to provide easy and superficial “fixes,” not to get caught up in popular ideas of the moment that may not have very much depth, but to create, study, develop and offer novel and thoughtful ways to understand, respond to and act under circumstances like these. Ideas that are pertinent have been evident in many sessions here, and the issue is making others aware of them. Our public relations director Ben Haimowitz’s work is very important in this and so is the new website that will enable us to link with our stakeholders more easily. But this is a matter for all of us to consider. The events of both last September and this spring and summer make it more crucial that we develop much more transparency, flexibility, and immediate accessibility in responding to corporate and societal issues on which we have something important to contribute.

Parenting

Second, there was a strong parental imagery present in the dream. The parents of my students owned the warehouse and I was shopping for shoes with Deborah Ancona. As I mentioned earlier, at the time of the dream Deborah and her husband’s four children were under the age of 7.

I know that parental images associated with organizations can sometimes be problematic, especially if they signal paternalistic or maternalistic approaches on the part of managers. I’m sure we all could describe very complicated relationships between parents and children, and other dysfunctional parental imagery. In the dream, however, the emphasis of the parental image was expansive and generative.

As I’ve paid attention to the parental image in the dream I’ve become aware that many of us in the Academy experience our work as “parenting” in one form or another. For example, at the Academy meeting each year Jone Pearce takes her former students out one night for “dinner on mom.”

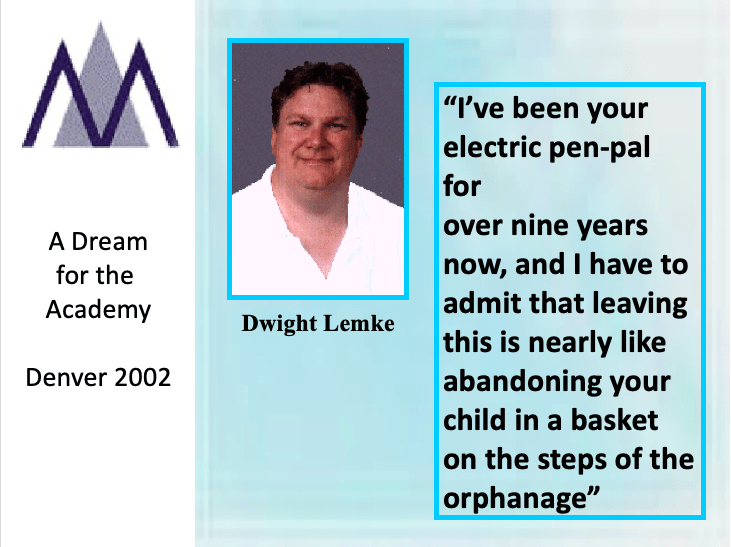

When Dwight Lemke “retired” from being web master for OMT to take on a similar role for AMJ, he wrote on the OMT listserve that “I’ve been your electronic pen pal for over nine years now, and I have to admit that leaving this is nearly like abandoning your child in a basket on the steps of the orphanage.”

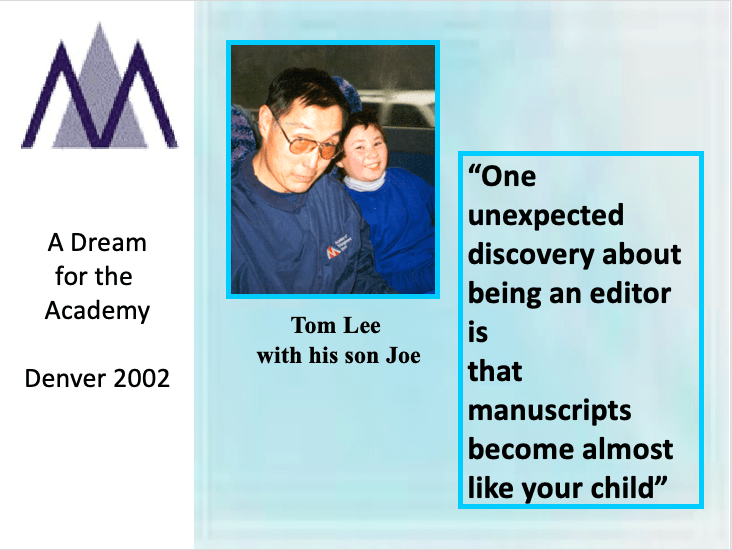

Tom Lee, the editor of the Academy of Management Journal, wrote me a note once in which he said that “One unexpected discovery about being an editor is that manuscripts become almost like your child.”

Granted, in terms of what I said above, the ways authors may experience editors treating their manuscript “children” is likely to be along the lines of “I know what is good for you even if you don’t.” But everyone who has submitted a manuscript to a journal knows how it makes a difference for a reviewer and an editor to think in a developmental way about authors’ work. This doesn’t require accepting a manuscript, but it does require respecting the work involved and looking to foster its further development.

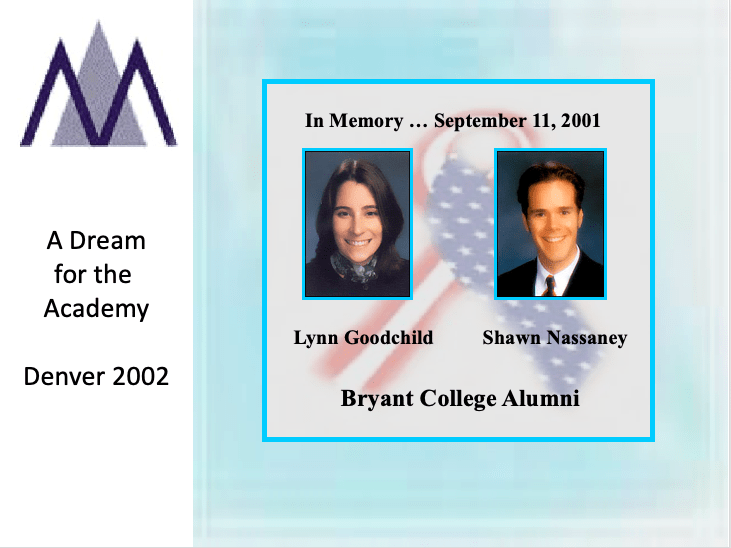

A particularly poignant example of parenting was posted by Professor Harsh Luthar of Bryant College on our “Academy cares” webboard last September shortly after the September 11 attacks. He described a vigil at Bryant College for two alumni, Shawn Nassaney and Lynn Goodchild who lost their lives that day. Lynn was a former student of his. He wrote that

After the vigil was over, I was taken to see Lynn’s mom. She is a beautiful person. We hugged. I said I was very sorry for her loss. I took out the crumpled roster of some years ago from my pocket and told her that Lynn was a good student. Lynn’s mom put on her glasses and in the faint light was able to make out Lynn’s name and she smiled.

We don’t typically describe the Academy or our work by means of parental imagery. It implies more extensive and a different kind of involvement and long term responsibility for our students, our research and research participants, our clients, our employees, even our colleagues, than we usually acknowledge. But I believe that being nurturing and developmental actually is at least a part of how we are with all these when we are at our best. And right now it is also an important contribution we can make.

A parental image suggests the importance of awareness of, attention to, and caring about those who are particularly vulnerable. This is in stark contrast to a myopic view in which the only ones who really matter, who are really even noticed, are high profile shareholders. Other groups that are more vulnerable, like, say retirees and their pension plans, employees, or younger people looking for work, don’t seem to be being considered at all by many corporations, a point that has been made by many speakers at this meeting.

A parental image also suggests a long enough time horizon to allow for nurturing and development. In corporations, if the whole system is focused only on the immediate, only on quarterly reports, without substantial attention to the long term as well, there isn’t time for such nurturing.

But short time horizons can be a danger for educators as well as managers. If we think that one ethics course taken by students is enough to train them to be able when they become managers to confront complex ethical dilemmas well we’re deluding ourselves. We need to develop ways of educating whose time horizon is an entire adult life, and in which our aim for young students is just to begin a process from which others will benefit later, as our graduates develop over their lives the ability to think more imaginatively and care more deeply about their organizations’ ethical behavior and the courage to act ethically in very complicated organizational situations. We also need to develop in doctoral students an awareness that research findings and new ways of conceptualizing can and should make a difference for good in the world. Thus, developing their craft over the course of a career in order to conduct research that matters is a worthwhile goal.

A shoe store on top of an apartment building

The third image is of shopping for shoes on top of an apartment building. This is a pretty contradictory, or paradoxical, image. Shoes typically symbolize something quite earthy and grounded, and, as I mentioned before, relate to journeys. The top of a tall apartment building, way up in the stratosphere, in contrast, often refers to a kind of ethereal, spirit world. We generally don’t go up into the stratosphere for something in “the real world.” In the dream, however, this ethereal world was precisely where the earthy, the grounded, was to be found.

We have many interesting dichotomies and contradictions present in the Academy. Here, though, I want to refer only to a few of the contradictions that seem particularly related to the dream image.

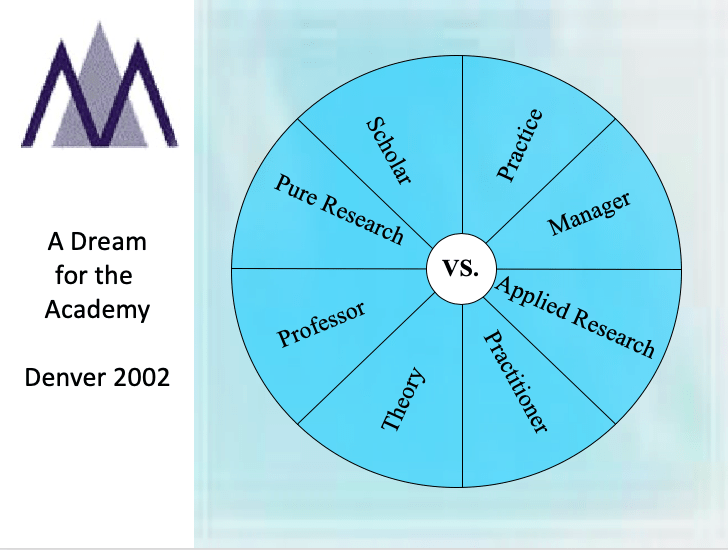

We talk about theory vs. practice. We distinguish between basic, “pure” research and applied research. We talk about scholar vs. practitioner, about professor vs. manager.

In one sense when we talk like this we’re distinguishing between the ethereal and pure vs. the ugly and muddy.

What might it mean to hold these various dimensions of research and practice in balance?

One of the interesting and, in fact, paradoxical effects of any kind of dichotomizing is that it simultaneously separates the poles from each other and links them together. In the case of the theory/research and practice divide, this dichotomy sometimes separates members, if divisions characterize other divisions by where they are on research/practice/ dimensions and if members so characterize other members.

But the dichotomy also links us together. When two sides of an issue, or two sides of anything are in conflict, they need each other for the conflict to carry on. Without research or practice or theorizing at one end of the spectrum, where would the other one be? The fact that the two are joined as well as separate enables creative development in understanding of the issues that give rise to the two poles.

One of the messages of the dream is that it’s pretty fruitless to try to tear apart these differing poles we experience and to choose one at the expense of the other. In the dream the shoe store was stuck to the top of the apartment building. In fact, in one sense, because it was on top of the apartment building, the shoe store was on an even higher ethereal plane, while the apartment building provided a strong foundation for it. There was profound intermingling between the earthy and the ethereal.

Maybe research vs. practice and its related dichotomies can be better thought of as tensions and dualities we all have in common, but that we express in different ways. This does not mean that theorists ought to abandon their work for bad practice or that practitioners should abandon theirs to undertake sloppy theorizing. It does mean developing an appreciation that whatever work we do we undertake within the context of the dilemmas and tensions we all share and to the understanding of which all of our work can contribute.

None of us are just brains producing words about important issues, and none of us are just bodies carrying out activities in a comparatively mindless fashion.

These contradictions are also relevant to what we might contribute to the current corporate crises. If we only take intellectual potshots at corrupt CEOs and other top managers without doing the research necessary to develop trustworthy new knowledge, we might feel self-righteous, but we’re not going to have an impact on what anyone else does. If we teach ethics courses without having any new ways to think about managerial quandaries and ethical issues, if we consult with organizations seeking help and don’t have anything really new to say to them, or if we are managers ourselves with no ways of imagining alternatives to current action we will not be contributing towards any true, substantive change. Helpful responses on our part require both our heads and our bodies. They require the imagination and skill to theorize well about different ways corporations and their managers can act and respond ethically to their stakeholders, and the circumstances that affect and are affected by these actions. They also require the capacity and courage to teach new kinds of responses and carry them out ourselves.

An underlying theme

A few months ago I suddenly realized that there was an underlying theme that links the three apparently quite separate symbols in the dream. It can be expressed in questions like the following: How much life and vitality does your work bring to you and to others? How abundant is the life it brings? The relationship between the dream symbols and this underlying theme may not be evident at first glance, but there really is a link, at least for me.

A parental image involves bringing life into being and nurturing it afterwards. A warehouse suggests the presence of resources to support that life, at least when they’re accessible and not stored away forgotten. A shoe store on top of an apartment building suggests that words that take on flesh, that are embodied, that walk, are more likely to be life giving than words that remain independent of what we actually do.

I think that an underlying message of the dream is the possibility and the encouragement it holds out to us that our work, our individual work and that of the Academy, can be life giving for us who carry it out, for the Academy as a whole, and for our stakeholders. We really do have within us as an Academy the resources to make a positive difference in the world for the profession of management whose advancement is our primary mission. We have the resources to do this now, in the midst of these corporate crises, and also in less troubled times.

I am not implying that our contributions are easy to make. They’re likely to be interwoven with tensions and dualities and apparent contradictions and not everything we do is going to succeed.

Moreover, simply having our work be life-giving and vital for us as individuals or as an Academy isn’t enough. There are a lot of people in a lot of institutions in a lot of places who are potentially affected by our work, and if it isn’t presented in a way that is alive for them, if we aren’t able to make available the resources we have in a way that’s interesting and engaging for others, if we can’t speak to tensions involving theory and practice in a way that brings life we are very limited and our contributions are impoverished.

Last March in a doctoral consortium Blake Ashforth commented that sometimes academics take very exciting, engaging, and important work they do and present it in such a way that it looks like a butterfly squished between two pieces of glass. That’s not very life-giving.

Maybe research reports, or teaching, or consulting reports, or managerial practice that squish a butterfly between glass deserve to be placed in cold storage, way in the back of the warehouse. Maybe we also need to develop new ways not only of opening the doors for others to come in, but also for sharing our work with them in ways that are lifegiving. With regard to the image Blake Ashforth was using, this might mean methods for describing the life of butterflies that preserve their grace and action across time, perhaps through a story that captures their beauty and the grace of their flight. Imagine how our work can have an impact if we can understand how to do this.

As for me at this point – I’m a little tired now at the end of this year of being president. But the sequence of offices I’ve held the past four years – with the role of past-president still left to come – has been bringing me on a complex journey that requires both theory and practice, that calls out of me resources I didn’t know I had, but that, most of the time anyway, I find within myself or, more likely several of the other people I have mentioned in this presentation, and that makes me aware of and very grateful for the abundant life in our Academy that I strongly hope that we will continue to nurture for our sake and for others’. Even if this work sometimes comes in the midst of very difficult times, I feel more alive, without doubt, than I did in December of 1997.

Mike, thanks very much for calling.