From the moment white boys and girls were born to slaveholding parents, enslaved people were to call the children Master or Mistress. Failure to do so resulted in punishment. Demanding deference from enslaved people was the first step in educating white children to manage and discipline enslaved persons. Instruction lasted from birth until adulthood as parents took every opportunity to demonstrate the proper “techniques” and demeanor needed for such a task. This took several forms – parents taught their children forms of discipline and management tactics and gave them slaves as gifts. By encouraging their children to follow their lead, enslavers raised the next generation of southern slaveholders.

In letters and diaries, slaveholding women recorded stories about raising their sons and daughters. These revealed three core stages in which white children learned slave management: receiving slaves as gifts or inheritance, punishment techniques, and the eventual awareness of the constructed racial hierarchy. It becomes clear that white southern children were not passive characters in the historical narrative of American slavery; they were active participants raised by their parents to be the next generation of slaveholders in the antebellum South.

It was common practice for slaveholding parents to give their children slaves as gifts in childhood. Several narratives and interviews share the stories of formerly enslaved peoples’ transfer from a slave-holding parent to their child. In one interview, an unnamed formerly enslaved woman describes being given to her master’s daughter. She was not surprised by this transaction since slaveholders often “made presents” out of enslaved people.

These transfers often happened at birth, with slaves given to infants upon their first breath. They were instructed to refer to the children as Young Master or Young Mistress, enforcing that white children had superiority and authority over enslaved people from birth. One chapter of Georgia Narratives tells the story of George Womble meeting his owner’s newborn child. His master instructed his slaves to “Go and pay their respects to the newly born white children on the day after their birth. They were required to get in line, and one by one, they went through the room and bowed their heads as they passed the bed and uttered ‘Young Marster,’ or if the baby was a girl, they said: ‘Young Mistress.'” Womble explains that deference to these children was expected since their status stood above his, regardless of age. Using incorrect titles was grounds for severe punishment. If the child was too young then their parents would conduct the punishment, but as children came of age they were instructed on how to take over this role.

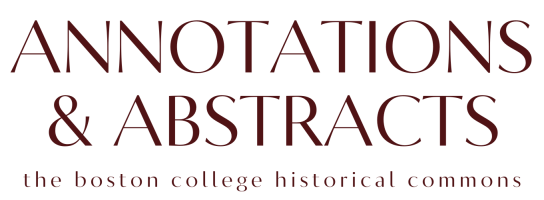

Federal Writers’ Project: Slave Narrative Project, Vol. 14, South Carolina, Part 2, Eddington-Hunter. 1936. Manuscript/Mixed Material. https://www.loc.gov/item/mesn142/.

It is important to note that enslaved people were required to call white children “Master” and “Mistress” rather than “Mister” or “Miss.” The delineation between the two indicated authority and control. “Mister” and “Miss” could refer to any young man or woman, but “Master” and “Mistress” implied ownership. Slaveholding parents did not take this difference lightly and punished slaves for misspeaking. Several accounts recall whippings and beatings for calling a child by their first name. However, even using the term “Miss” was grounds for physically reprimanding Rebecca Jane Grant, a formerly enslaved woman. “Marster Henry was just a little boy about three or four years old… [They] wanted me to say ‘Marster’ to him – a baby!” Her mistress repeatedly beat Grant with a cowhide strap, reiterating that her son’s title would not be forgotten. The human property white children acquired in childhood followed women into their marriages, at which point their fathers often gifted them more slaves to increase their value as potential wives.

The second step of raising a young slaveholder was instruction on management and punishment. This process began at a very young age when children would purposefully observe the actions of their parents. Fathers encouraged their children to watch them punish their slaves from afar. In an 1863 interview with the American Freedmen’s Inquiry Commission, a former slave from South Carolina described Mr. Farrarby whipping and kicking an enslaved cook after she burned a meal. Farrarby’s young children observed the entire scenario through the window despite the blatant brutality. Even in more extreme cases, when victims died from their punishment, children were not deterred from watching. More important than the emotional trauma an adolescent might receive from such an instance was their understanding of “the relationships among slave mastery, discipline, and violence.”

When parents deemed they were old enough, children partook in physical punishment, whether they joined their parents or disciplined their slaves on their own. The violent story of Henrietta King, a former slave who served as a caretaker for a young woman in Virginia, describes a beating from the child that left King permanently disabled and disfigured. After King was caught stealing from the child’s bedroom, the young girl pinned King’s face with a chair and whipped her repeatedly. Following the assault, Henrietta King’s jaw was permanently damaged, leaving her unable to eat or speak properly. The child, eventually distressed by the harm she caused, begged her parents to give King to a family member on another plantation. In They Were Her Property: White Women as Slave Owners in the American South, Stephanie Jones-Rogers posits that the event may have permanently impacted both the victim and the aggressor. “It’s clear that this event affected the rest of King’s life, but what about her mistress’s daughter? If the testimony of formerly enslaved people offers any evidence, we can be assured that in one way or another, this experience affected the way she treated the slaves who came under her control late in life.” Part of these children’s slave-owning education centered on balance: when to punish and when to show mercy. Through trial and error and parental guidance, these children developed the techniques to become commanding slaveholders.

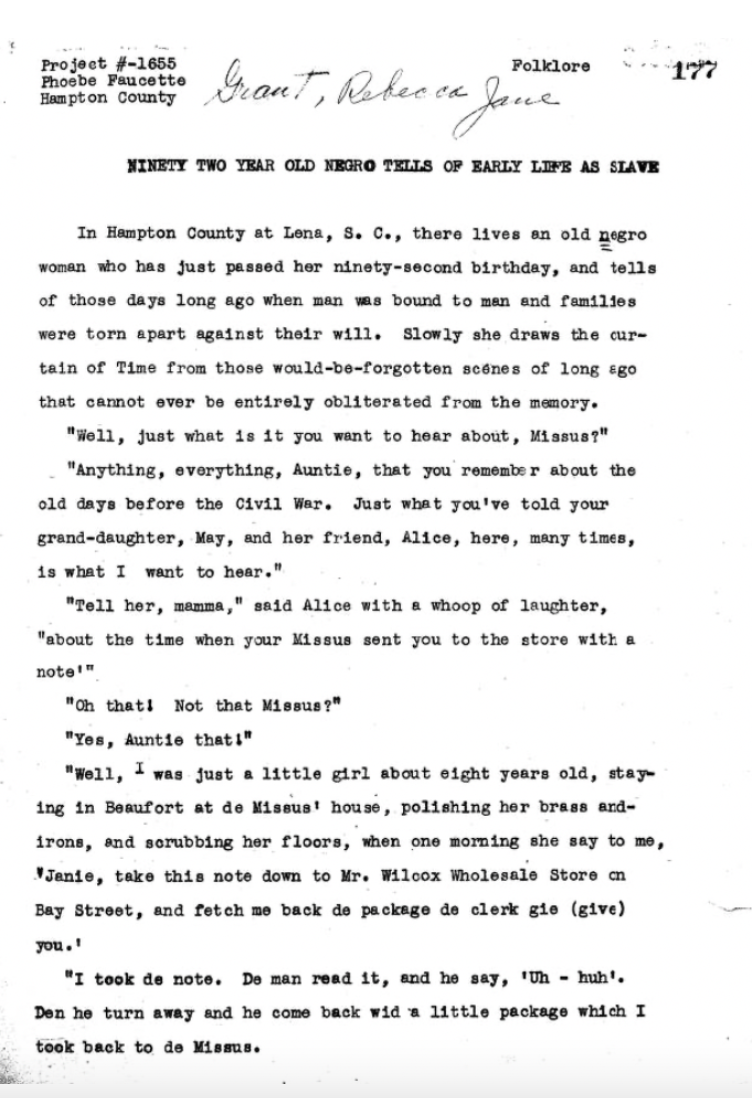

While most slave management education came from slaveholding parents, one woman rose to fame in the early 1830s as a maternal figure to southern children. From Charleston, South Carolina, Caroline Howard Gilman began editing her juvenile paper, The Rosebud. The Rosebud was a weekly editorial composed of poetry, short stories, and songs written mainly by Gilman with her daughters in mind. Following her pro-slavery views, Gilman also published critiques of abolitionist literature and instructional pieces for young slaveholders primarily aimed toward young girls to serve as supplemental education.

Copy of The Rosebud, Front Page, published on October 4, 1834. Accessed via HathiTrust.

In an edition of a series titled “For My Youngest Readers,” Gilman published “The Country Visit: The Little Negroes.” The chapter depicts the main character, Clara, watching her mother give food and tobacco to their slaves. Clara took note of her mother’s actions before her mother said, “When you are sixteen years old, you must help me as I did your grandmama.” Emboldened by a sense of responsibility, Clara asked her mother if she could help her that day. With permission, Clara gathered the slaves, passing out biscuits and sugar. As they began to eat, Clara commanded them to stop and “make cutchy,” meaning curtsy or bow, and thank Clara for her offerings. The children followed her order, then Clara allowed them to eat. Their obedience pleased her and encouraged her education in slave management. Those young southern children reading Gilman’s work likely felt that same encouragement.

In a more interactive column, Gilman reported the happenings of her “Editor’s Monthly Tea Party.” The pages show a script-like conversation between Gilman and several white southern children who join her to discuss The Rosebud and their daily lives. Though he is not the centerpiece of the conversation, Gilman orders about an enslaved man named Marcus several times. Marcus retrieves tea for the party and brings napkins when young Maria spills her teacup. Marcus has no spoken lines. His actions appear in parentheses through interactions or Gilman’s stern instructions, which litter the page: “Marcus, bring tea. (Exit Marcus),” “Enter Marcus with tea,” “Quick, Marcus.” Gilman’s lesson to the children in this passage lies beneath the explicit conversation as she exemplifies how an enslaver should address a slave. The children observe, learning from Caroline Howard Gilman in person, while so many other southern children learned from afar through her publication.

Caroline Howard Gilman, author of The Rosebud. Painted by John Wesley Jarvis, 1820. Public domain.

The message of plantation education was clear: white children had power over black slaves because of their whiteness. Explicit or otherwise, this ideal was evident throughout the instructional process of white southern adolescents. Understanding the constructed racial hierarchy in the antebellum South was the third step in becoming a young American slaveholder. Sarah Butler, daughter of slaveholder Pierce Kemble and wife, and eventual abolitionist, Fanny Kemble, came to this understanding at only three years old. In a letter to a friend, Fanny described Sarah’s exchange with her chambermaid. “Some persons are free, and some are not…I say, I am a free person Mary – did you know that?” Mary replied obediently, “Yes, missis, here…I know it is so here, in this world.” At such a young age, Sarah began to wrestle with the ideas of racial hierarchy through her interactions with her family and their slaves. Sarah, along with the other children of the antebellum south, absorbed the instruction passed down to them from adult figures in their lives. They reckoned with the idea of slavery through this instruction, making decisions about how they would treat the slaves given to them by their parents. White parents invested in this education, or indoctrination, assuring their children would further the institution of slavery.

Works Cited

- “Interview with Jennie Fitts,” in The American Slave, edited by George P. Rawick, 5:4, Texas Narratives, 1325. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 1979.

- Jones-Rogers, Stephanie E. They Were Her Property: White Women as Slave Owners in the American South. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2020.

- “Interview with George Womble.” Federal Writers’ Project: Slave Narrative Project, Vol. 4, Georgia, 1936.

- “Interview with Solomon Bradley.” American Freedmen’s Inquiry Commission, South Carolina, 1863.

- Howard Gilman, Caroline. “The Editor’s Monthly Tea Party No. 1/” The Rose Bud, or Youth’s Gazette. October 06, 1832.

- Howard Gilman, Caroline. “For my Youngest Readers: The Country Visit, Chapter 7, the Return,” Southern Rose Bud. August 23, 1834.

- “Interview with Tines Kendricks.” Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers’ Project, 1936-1938, Vol. 2, Arkansas Narratives.

- Jane Grant, Rebecca Jane. “Hurmerence,” Before Freedom, When I Just Can Remember, 1989.

About the Author

Emma Van De Wiele (she/her) is a second-year master’s candidate in the History Department at Boston College. Her research focuses on the southern United States in the 18th and 19th centuries with a specific focus on women and children in the plantation household. She aims to emphasize informal modes of education in the South, namely those which promoted the constructed racial hierarchy between black and white southerners.