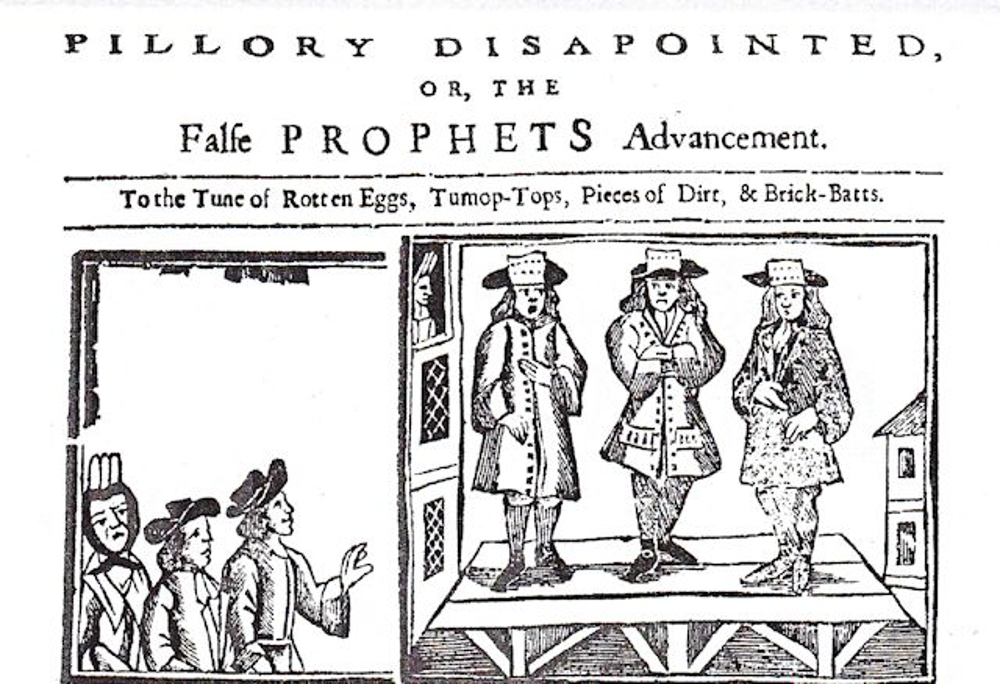

When the Camisards fled to England, their Protestant ally, they attracted a lot of attention, especially as they began to convert English Dissenters from the middling and upper classes, who adopted their sensational practices. Some of the new English converts were very well connected, such as Justice of the Peace, John Lacy, and there is evidence to suggest that some members of the nobility in England, Scotland, and France belonged to this sect. However, by 1707 the French Prophets had come under attack. Some of their leaders, prophets and ex-military leaders in the Camisard Uprising, Elie Marion, Durand Fage, and Jean Cavalier of Sauvé, faced investigation as imposters and were eventually put on display in a pillory. This investigation attracted the sympathies of Misson, who eventually became a French Prophet himself. With the close help of translator and fellow French Prophet, John Lacy, Misson put together a collection of testimonials of the wonders and miracles that took place in the Cevennes from interviews with members of the French immigrant community and published them for a London audience. Misson’s original work, Le Theatre Sacre, was for the French Huguenot population in London, and the translation by John Lacy, A Cry from the Desart: Or, Testimonials of the Miraculous Things Lately Come to Pass in the Cevennes, Verified Upon Oath, and by Other Proofs was for the English dissenting communities from which they drew most of their support.

Perhaps the most interesting feature of the testimonials in A Cry from the Desart is how many accounts it contains of child prophets, especially under the age of ten. This is significant because despite the large body of scholarly work that has been done on early modern beliefs about prophecy, and female prophecy in particular, few historians have focused on young children who participated in this type of religious experience. Lack of research on this particular topic is even more unusual considering the common observation made by scholars writing about the Camisard rebellion that most of the prophets were children. Examining these testimonials is useful because they can provide us with valuable information about early modern beliefs about child prophecy and how religious communities thought prophecy worked in general. The testimonials also provide us with insight into particular ways the author and translator chose to portray the refugees to a London audience. Accounts of families prophesying together shed light on family dynamics in France at an interesting moment in time when a series of legal interventions were made by the state in an attempt to minimize and in some cases do away completely with the influence of nonconforming parents and to ‘re-educate’ their children in the ‘proper’ religion.

Historians such as Anna French have suggested that according to early modern folk wisdom, children made better prophets. The reason for this was that people thought that because of their purity, physical frailty, and closeness to God (those near birth and those near death were both thought to be closer to the other side) that they made better ‘vessels’ for the Holy Spirit to inhabit. John Lacy’s book, In Defence of Prophecy, in which he outlined the belief system of the French Prophets in England reflected these views of prophecy and youth. There seemed to be an expectation within these early modern dissenting cultures that children might be more likely to be endowed with spiritual gifts such as the ability to prophesy than adults.

Despite the common expectation that children made better prophets than adults, there were other, more practical reasons for the author to frame the collection of testimonials in a way that drew so much attention to child prophets. The first reason is that the collection of testimonials was a direct response to public accusations that French Prophet leaders, Elie Marion, Durand Fage, and Jean Cavalier of Sauvé were imposters. Historian Lionel Laborie suggested that John Lacy argued child prophets were considered more believable than adults because it was less likely they were faking their dramatic manifestation of spiritual gifts.

The focus on children also suggests that the author sought to lessen the association between Camisards and military activity in France. In 1707, when these testimonials were published, Francophobia was on the rise during the War of Spanish Succession. During this period, French immigrants faced persecution as the English made no distinction between their papist enemies and the Protestant refugees. By focusing on children and families over warrior prophets, Misson portrayed them as harmless and virtuous. This would have also perhaps helped diverting attention from rumors that were circulating at the time that Camisard prophets had been involved in atrocities during the rebellion.

Another reason the author may have chosen to focus on children so much was that he was trying to attract converts from the English Dissenting community. During the early 18th century, there was a popular genre of Dissenting fiction which served as instructional manuals for proper behavior which included the trope of the “saintly child.” One prominent author of works such as this was Daniel Dafoe. By presenting the testimonials in a genre that was popular at the time, Misson and Lacy could have attracted a larger readership and increased the likelihood of attracting new followers.

Although it is easy to focus exclusively on Misson’s testimonials and try to explain them as a general appeal to an English audience, according to Brian Strayer, the French records show that French authorities also commented on the large number of child prophets during the rebellion. French officials first thought the inhabitants might be suffering from some disease or psychological contagion due to the dramatic physical symptoms they exhibited and sent physicians out to examine them (their initial interpretations did not differ much from historians who have postulated the Camisard’s religious ecstasy was the result of ergot poisoning or mass hysteria). Once they established they were religious ‘Fanaticks’ and not physically ill or mad, they thought the parents must be coaching children in this behavior.

With a few notable exceptions, such as an eight year old boy prophesizing from a fortress in which he was imprisoned, most cases of child prophecy in A Cry from the Desart included parents, siblings, and cousins. Entire families were described as developing spiritual gifts around the same time. Rather than children developing the gifts first, however, as one might expect if this story was just being told to meet popular expectations, adults and older siblings tended to develop the gifts first, suggesting they indeed may have modeled the behavior for younger family members.

This is significant because it suggests that parents and older siblings did coach younger generations, reflecting a possible backlash to some particular legal actions posed by Louis XIV aimed at re-educating children of religious nonconformists in the Catholic faith and in some cases removing them from their parent’s household and placing them with a Catholic relative, a convent school, or Catholic reeducation center. Though most parents outwardly ‘abjured’ their faith, authorities remained suspicious. There was, indeed, a long tradition of Huguenot families educating children in the faith in secret in the home. Like Huguenots and English Catholics during the reign of Elizabeth I, religious persecution and intervention in family life likely only served to push Camisard families closer together, producing the opposite effect as the authorities intended. One possible explanation of child prophecy is that it was, in some way, orchestrated by parents as a means to regain a sense of control and family cohesion they felt was under threat.

While Anna French would emphasize the agency of the child in most cases of child prophecy, it is not unlikely that parents incentivized the children in the Cevennes not to give up their family’s traditional faith by giving them special attention. In acting as a unit, and encouraging children to deliver prophecies, they probably also thought they would be less likely to be harshly punished than adults acting alone, especially in the beginning when prophecy was not formally outlawed. Sadly, accounts suggest that children could not count on their age for safety. There are accounts of children being imprisoned, send to work as galley slaves, and some cases even executed, although these numbers were much greater for adults. However, very devout Camisard parents likely prioritized the salvation of their children’s souls over physical safety. It is interesting to note that in comparing cases of child prophecy that occurred in France, as described in A Cry from the Desart with those in London, a far greater emphasis was placed upon children and families in France. In London, when accounts of child prophecy did appear, say, in the writings of John Lacy or other French Prophets, children were mentioned on their own, not usually mentioning their family. In A Cry from the Desart, children in France were presented as religious leaders, holding assemblies, and as being taken very seriously by adults. In England, however, adult men such as Lacy, Misson, Marion, Fage, and Cavalier held the most influence, and child prophets, though not uncommon, were viewed more as curiosities than legitimately revered by large groups of adults. This further supports the idea that child prophecy in France was linked to a mass, popular resistance to policies that were interfering with family life.

Works Cited

- Crackanthorpe, David. The Camisard Uprising: War and Religion in the Cévennes. Oxford: Signal Books, 2016.

- French, Anna. Children of Wrath: Possession, Prophecy, and the Young in Early Modern England. New York: Routledge, 2015.

- Laborie, Lionel. Enlightening Enthusiasm: Prophecy and Religious Experience in Early Eighteenth Century England. Manchester, United Kingdom: Manchester University Press, 2015.

- Strayer, Brian E. Huguenots, and Camisards as Aliens in France, 1598-1789. Lewiston, NY: the Edwin Mellon Press, 2001.

- Underwood, Lucy. Childhood, Youth and Religious Dissent in Post-Reformation England. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

About the Author

Sarah Ahmed (she/her) is currently a master’s student in the History Department at Boston College. Her

research focuses on Modern European History, but centers mainly around 18th and 19th century

Britain. She is especially interested in topics concerning the Enlightenment, religion, Revolution,

the development of early psychology, and changing perceptions of self.