Celtic languages have declined significantly in the last millennium despite once dominating the British Isles. The Irish language especially has diminished significantly despite once covering the whole of Ireland. Many scholars have attributed this decline to political, economic, and social factors, but the role of religion remains underexplored. The 16th through 18th centuries in particular are indicative of the influence of religious institutions as, in the wake of the Protestant Reformation, religion motivated many policies towards Irish language speakers. Throughout this period, the Irish language was constantly affected by pressures from religious institutions. However, even before the Protestant Reformation, Irish was at the center of a multitude of struggles occurring in Ireland.

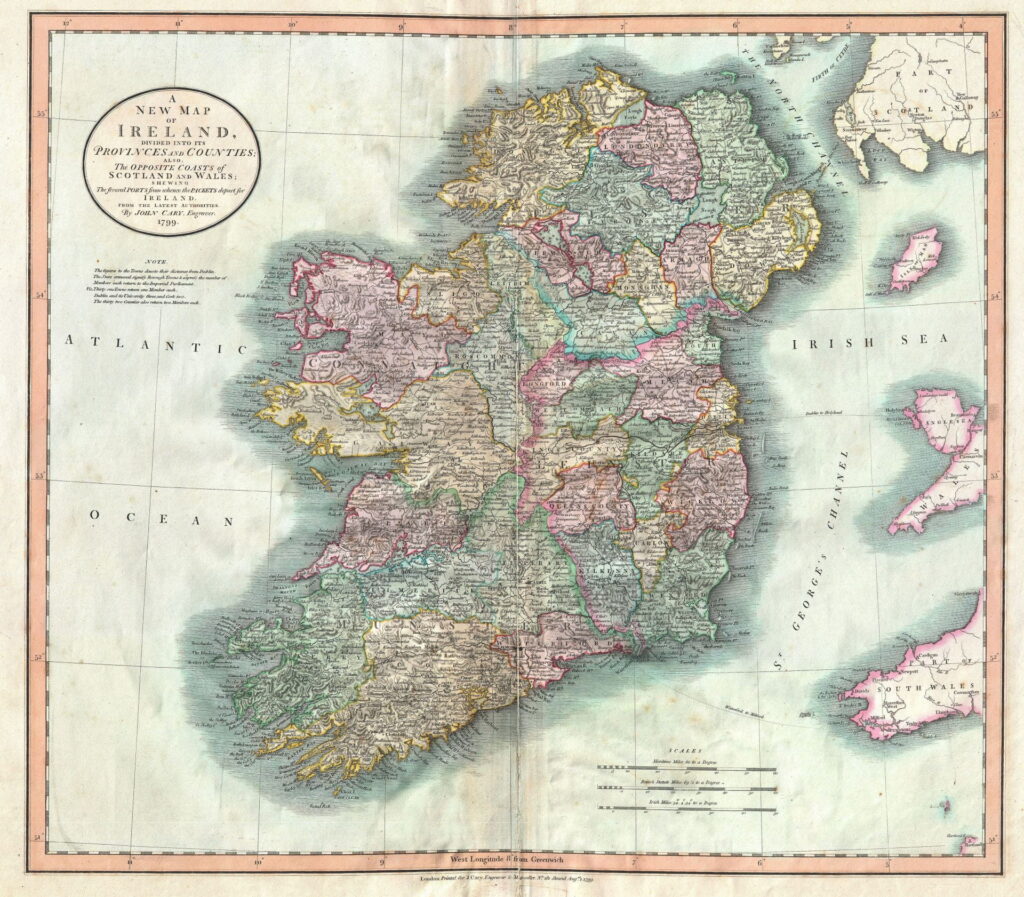

The 1169 Norman invasion of Ireland brought new languages like early English to the island and was the start of the pressures against the Irish language. However, English control of Ireland was limited to the east around Dublin. By the 14th century, English control had waned and a Gaelic resurgence began. Many of the Anglo-Norman settlers in Ireland had become Gaelicized, and spoke the Irish language. To combat this de-anglicization, King Edward III of England issued the Statute of Kilkenny in 1366 to ban the Irish language within English-controlled areas. The statute did not seek to suppress the Irish language among the Irish, but rather among the English in Ireland. Until the early 16th century, there were few other attempts to control the Irish language.

When King Henry VIII took the throne, however, he wanted to reestablish control over Ireland both politically and religiously as part of the English Reformation. He hoped that by anglicizing the Irish people in language and culture, he could also bring them into the Protestant Church of Ireland and make them loyal English subjects. Towards this end, he passed An Act for the English Order, Habit, and Language in 1537 prohibiting the use of the Irish language, ordering education in English, and requiring religious preaching in English. An important element of this act was the implication that language was tied to political loyalty. The king’s insistence that speaking Irish, not English, was an indication of disloyalty would continue to influence linguistic policy in Ireland in the coming centuries.

After the Protestant Reformation, most of the population of Ireland remained Catholic. Because of this, the Irish language became tied to Catholicism, aligning it with not only political but also religious disloyalty. Protestantism as a movement believed in the importance of worship in vernacular languages. The desire to use vernacular languages inspired many within the Church of Ireland to try using the Irish language in worship as a means of converting Catholics. However, this aim was frustrated by the limited number of Protestants who had learned the Irish language in addition to a lack of religious texts in Irish. These texts would be necessary in order to ensure uniformity of worship among any converted Irish speakers. To this end, the first religious text printed was Séon Carsuel’s 1567 Foirm na nUrrnuidheah, a book of common order. However, because Carsuel was a Presbyterian, the Anglicans in the Church of Ireland printed their own text in 1571, an Irish alphabet and catechism. These texts began the process of Protestants using the Irish language.

Throughout the 17th century, religious institutions further attempted to use Irish in order to reach Irish speakers. Following the 1607 Flight of the Earls, bards, the traditional keepers of the language, lost their influence and the Irish language began to change. This period of language instability allowed priests to try taking control of the language in order to use it for their religious goals. Even the Catholic Church, which hadn’t taken advantage of vernacular printing in the 16th century, began printing religious texts in 1611, but because they were published by exiled Catholic priests on the European continent, they rarely reached Ireland. In Ireland, however, members of the Anglican Church of Ireland began working on a translation of the Bible into Irish and published the New Testament in 1602. After significant delays, the church also published an Old Testament in 1685 with a full Bible following in 1690.

By the start of the 18th century, changes in the political and religious situation throughout Britain greatly affected the Irish language. After the Glorious Revolution in 1688, Great Britain was confirmed as a Protestant kingdom. In Ireland, this led to the penal laws punishing Catholics and Dissenters, non-Anglican Protestants. Because many Catholics had rebelled against the new king, Catholics were branded political enemies, and since many Catholics still spoke only Irish, this affirmed the idea that speaking Irish was a mark of disloyalty. Religion became increasingly tied to culture and language, leading to greater influence of religion on the Irish language.

The population of Ireland at this time mainly belonged to three religious denominations: the Church of Ireland, the Catholic Church, and the Presbyterian Church, the latter of which was concentrated in Ulster. Although both Catholics and Dissenters were punished under the penal laws, Catholics were considered political enemies in a way that Protestant Dissenters weren’t. Additionally, because most Presbyterians came from Scotland as part of the Ulster Plantations, they spoke English, so they were not enemies linguistically or culturally. However, the Presbyterian Church did briefly proselytize in Irish starting in 1716, but within a few decades, few clergy used the language. Likewise, the Catholic Church used Irish minimally. Although it had printed a few religious texts in Irish in the 17th century, few copies reached Ireland from the continent. Moreover, because Latin was the church language, Catholic clergy did not use Irish in their services. By 1795, when the Catholic seminary at Maynooth was founded, English was the only language of instruction.

As for the Church of Ireland, there were many members that believed in using Irish for conversion and advocated for vernacular preaching and printing. While the church did allow Irish preaching starting in 1634, there were limited Irish-speaking Protestant clergy. There were hopes to train Irish-speaking clergy at the newly founded Trinity College in Dublin, but that program saw little success. Despite these efforts, the Church of Ireland never fully embraced most of the suggested Irish language programs. Many believed that using the Irish language would reinforce the divide between the English and Irish culturally, politically, and religiously. Some priests disagreed, claiming that using Irish to convert would actually lead to the eventual adoption of English culture and language by the Irish people. However, even these men usually reinforced the idea that the ultimate goal of using Irish was to remove it in favor of English. By 1800, the Church of Ireland had largely abandoned the use of the Irish language, much like the Presbyterian and Catholic churches.

Religious institutions significantly influenced the Irish language from the sixteenth through eighteenth centuries. As the 19th century began, education became the arena of change for Irish, but it should be noted that churches played a huge role in education at this time. The Irish language was deprioritized if not outright banned in most schools. Many Protestants attacked the Irish language for its association with Catholicism, hoping to defeat the language through neglect. When Ireland gained its independence, many in the government blamed the decline of the Irish language on the national school system, which was founded in 1831 and used only the English language. However, this claim ignores the fact that even before the national schools, religious institutions, even the Catholic Church, largely ignored the Irish language in both education and worship. Within the religious sphere, many individuals had aims to either preserve or destroy the Irish language, but neither goal fully succeeded by the modern era. Instead, the language entered an era of revitalization rather than preservation that continues today. While religious institutions in Ireland are still influential, especially in education, they will never again hold the sway over the Irish language that they did before the 19th century.

Works Cited

- Crowley, Tony. The Politics of Language in Ireland 1366-1922: A Sourcebook. Edited by Tony Crowley. Routledge, 2002.

- Crowley, Tony. Wars of Words: The Politics of Language in Ireland 1537-2004. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Durkacz, Victor Edward. The Decline of the Celtic Languages: A Study of Linguistic and Cultural Conflict in Scotland, Wales and Ireland from the Reformation to the Twentieth Century. Edinburgh: John Donald Publishers, 1983.

About the Author

Rowan Bianchi (they/them) is currently a master’s student in the History Department at Boston College. Their initial interest in Irish history was sparked when they studied at Trinity College Dublin and now they are interested in early modern Ireland with a particular focus on religion. Rowan is also learning the Irish language and hope it will further their historical understanding of Ireland. Follow Rowan on Twitter @RowanBianchi.

To stay up to date on all things Annotations & Abstracts, follow us on Twitter @bchistcommons.

Heya i’m for the first time here. I came across this board and I find It really useful & it helped me out a lot. I hope to give something back and aid others like you aided me.

Hi there, I enjoy reading through your article post.I like to write a little comment to support you.

Don’t miss out on this amazing resource. Click the link and unlock your creativity!

This site was… how do I say it? Relevant!! Finally I havefound something that helped me. Cheers!

I love how this blog consistently motivates and uplifts its readers.

Hello my family member! I want to say that this post is awesome, great written and come with almost all vital infos.I’d like to see extra posts like this .

I’m unsure about the bullet points.. seems a bit forced.

Ꮲretty ցreat рost. I simply stumbled

upon your weblog and wished to mention that I’ve truly loved browsing your weblog posts.

In any case I’ll be subscribing for your rss feed and I hope

you write ɑgain very soon!