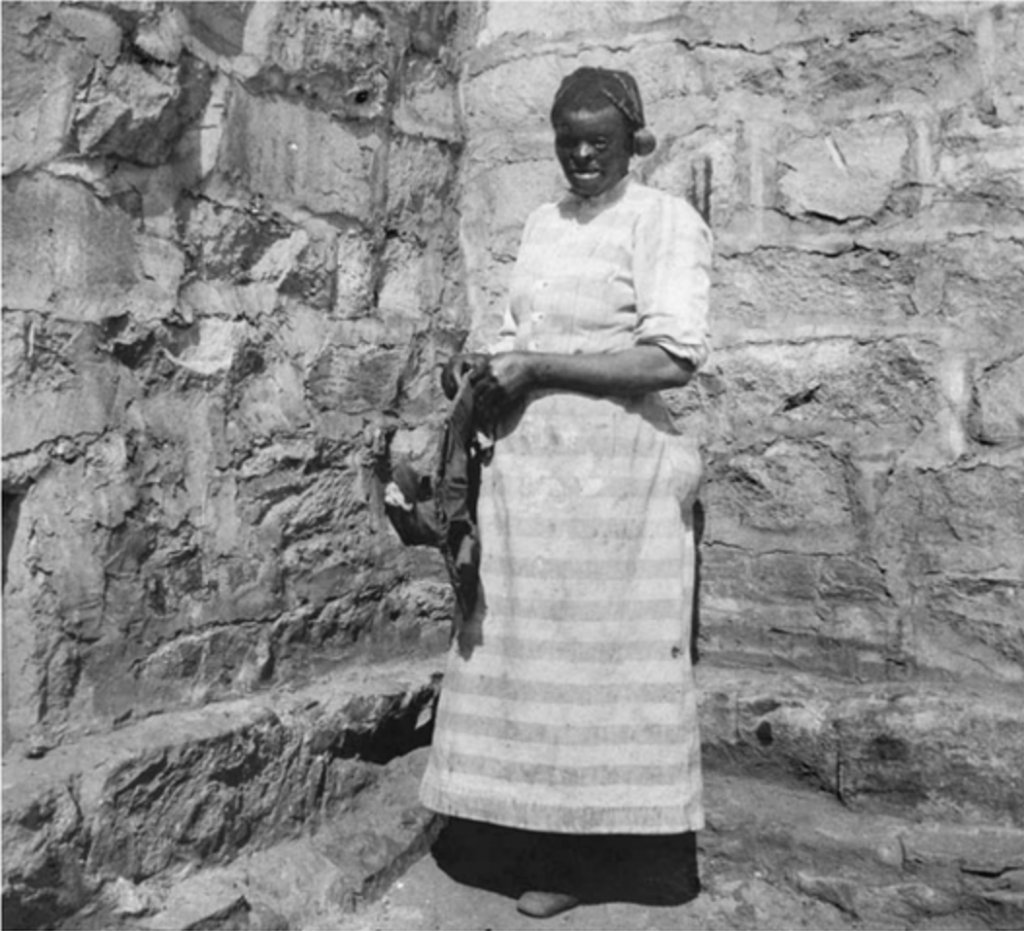

Her name was Eliza Cobb, and even though she was born at the onset of emancipation in 1866 her life was composed of very little that resembled anything close to freedom. At the age of twenty-two Eliza was raped, became pregnant, and later that year was arrested by police and sentenced to work at the Du Bois sawmill camp on the unproven charge of infanticide. After working at the sawmill camp for a few years, Eliza was transferred to Milledgeville State Prison Farm in Georgia where she, along with hundreds of other imprisoned Black women, once again experienced the horrifying intersection between pregnancy, race, violence, and criminalization. Sadly, these crossings would not end at the turn of the twentieth century, but instead have continued to haunt the evolution of the American prison system and state-led violence against maternal health and reproduction.

Most people tend to think of pregnancy and motherhood as special, sacred even. And while this idealism is certainly compelling, it’s also far from the lived reality that untold numbers of predominantly Black and Brown women have experienced since the moment the photo of Eliza Cobb was taken.* Indeed, throughout the twentieth century pregnancy, maternal health, and reproduction have become increasingly intertwined with state policies that are dictated not by public health and social welfare, but instead by power, violence, and the criminalization of non-normative pregnancies and families. Reproductive bodies have literally become the state’s business.

It’s highly unlikely that when Eliza was sent to work at the saw mill camp in 1889 she was aware that Southern lawmakers a were “institutionalizing gendered racial terror as a technology of white supremacist control.” This “institutionalization” was a way of exploiting gendered forms of labor to help create the “New South” following the destruction wrought by the Civil War. Female along with male convict laborers were forced to work in coal-mines, on railroads, brickyards, sawmills, and plantations. They were often contracted out by the state to private companies and individuals in a practice known as “convict leasing.” Although convict leasing was eliminated in 1908 its replacement was no better. On the chain gang, imprisoned men and women continued to be a main source of labor as the South sought to rebuild its infrastructure, encourage economic development, and reinstate the fear and gendered-racial ideologies that supported white supremacy.

The “New South” was undoubtedly created by every brick that was laid, railroad track that was put down, and lumber that was sawed to build new homes and businesses. But the South, and, by extension, parts of the state and federal government were refashioned on something even stronger than brick and steel. The mythologies of Black female deviance, sexual monstrosity, and inability to achieve the ideal of white motherhood was the mortar upon which state-sponsored violence and the criminalization of Black women’s pregnancies were kept together. By controlling the forced labor of Black women, disproportionately arresting Black and Brown women compared to white women, relying on sexual violence and terror to maintain order, and providing little if any support for women who were already pregnant or became pregnant while incarcerated, states reinforced the reproductive-carceral logic that idealized white feminine sanctity and white supremacy. As Sarah Haley writes, “through policing, legislation, and judicial enforcement, Black women were made juridical inverts,” or bodies that were undeserving of protection, reproductive care, and socio-cultural acceptance.

Of course, one of the most unfortunate aspects about these mythologies, erroneous beliefs, and prejudices (beyond the obvious human rights violations), is the degree to which they persist and shape-shift according to their respective time and place. Given that lies based on fear and self-interest are often the hardest ones to dispel, the narrative of Black women’s reproductive deviance combined with state violence continued to inform state and federal policy well into the mid-late twentieth century.

Take, for example, the energetic proposals in the early 1990s of using Norplant, an implantable form of birth control, as a way of limiting the number of children born to women receiving welfare or who were on Medicaid. Lawmakers in certain states actively went beyond just making Norplant more accessible to low-income women. Numerous bills were designed to pressure women by offering financial incentive or “requiring implantation as a condition of receiving benefits.” In Kansas, Connecticut, and Louisiana, state representatives Kerry Patrick, Robert Farr, and former-Klu Klux Klan Grand Wizard David Duke respectively all either proposed or encouraged legislation that would give women on welfare money to have the device implanted and then a set amount of cash each year the woman kept using the device. Although by 1997 no state legislature had passed a bill either mandating Norplant or offering financial bonuses for its use, legal scholar Dorothy Roberts ellucidates how state welfare rhetoric combined with persistent cultural myths “blames Black single mothers for transmitting a deviant lifestyle to their children.”

Of course, this leveling of blame, guilt, and shame doesn’t just stop at racial and class boundaries. All women are impacted by it, whether they are white or BIPOC, educated or uneducated, rich or poor. Whether a group of women is being used as the social “ideal” of what motherhood should look like or its foil, the reproductive lives of all women become bound up with the goals of the state. Throughout the mid-late twentieth century women who failed to meet the political and socio-cultural “standard” of reproductive and maternal health could expect at best a lack of support and at worst coercion, surveillance, and violence through the form of state-sponsored agencies and an imbalanced criminal justice system. Given the current threat to reproductive justice once again at both state and federal levels, this issue has sadly not simply remained a “thing of the past.”

If we are going to continue fighting these injustices and ensure that pregnancy ceases to be punitive, then we must not only elect legislators who truly represent our communities but also advocate for a social welfare system that is fully equipped to meet the needs of all women, wherever they are in their lives. We can no longer continue to rely on a system that medical anthropologist and OBG-YN Carolyn Sufrin refers to as “jailcare,” or the “disturbing entanglement of carcerality and care” for pregnant people who find that the only place they can receive even basic prenatal care is behind bars. Although many of these women are in jail because of drug abuse or other low-level crimes, to use their offenses as a way to deny responsibility for their and their fetus’ welfare is an unfortunate example of focusing so much on individual trees that you lose sight of the forest. That poor, oftentimes homeless pregnant women sometimes choose to go back to jail for prenatal care is a symptom of “a historical tragedy that is peculiar to the United States . . . defined by the whittling away of public services for the poor, coupled with an escalation in the number of jails and prisons serving as sites for the care of that same population.” To dismiss people who are pregnant, drug addicted, poor, homeless, and in jail as weak, immoral, or somehow deserving of their situation is blind and short-sighted. While personal responsibility is important, if it is not also balanced by an understanding of how all of our choices are shaped or limited by larger circumstances then we miss crucial opportunities for compassionate change that can offer hope, dignity, and a better way forward.

What good is our history to us if we do not use it in ways to make lives better for our friends, family members, and communities today? We know that how our legislative, criminal justice, and welfare system have operated together in the past hasn’t always worked, to say the least. And to have this dysfunction and violence, whether intentional or not, inflicted on pregnant people is to miss how we have the ability to change these systems. They were created by human beings and so there is always the potential for change. I have hope that those elected to state and federal positions who bring energy, passion, and new ideas will continue to, however incrementally, push for legislation that cares for, protects, and celebrates reproductive and maternal health. Such a reality was inaccessible for Eliza Cobb, but we can honor her and so many other women’s stories by making it real for us.

Works Cited

- Haley, Sarah. No Mercy Here: Gender, Punishment, and the Making of Jim Crow Modernity. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 2016.

- Roberts, Dorothy. Killing the Black Body: Race, Reproduction, and the Meaning of Liberty. New York: Pantheon Books, 1997.

- Sufrin, Carolyn. Jailcare: Finding the Safety Net for Women behind Bars. Oakland: University of California, 2017.

*I acknowledge the implicit error that comes with using the pronoun “she” when talking about pregnancy and motherhood, as I realize that not every pregnant person or mother identifies as female. My use of specific pronouns is in no way meant to ignore or deny the multiplicity of people who can become pregnant and act as mothers. I also recognize the inherent complexity that accompanies the word “experience” and the myriad factors that comprise a person’s perceived reality; due to the length of this post I have chosen not to explore these factors here.

About the Author

Meghan McCoy (she/her) is currently a master’s student in the History Department at Boston College. Meghan’s research interests are focused on the history of maternal health, childbirth practices, and midwifery in the United States from the late nineteenth century to present day. She hopes that by delving into this history while engaging with other individuals and organizations committed to maternal health care, she can contribute to the work needed to eliminate disparities and ensure equitable treatment.

To stay up to date on all things Annotations & Abstracts, follow us on Twitter @bchistcommons.

I’ve been exploring for a little bit for any high-quality articles or blog posts on this kind of area . Exploring in Yahoo I at last stumbled upon this site. Reading this info So i am happy to convey that I have an incredibly good uncanny feeling I discovered exactly what I needed. I most certainly will make sure to don’t forget this website and give it a glance regularly.

I wanted to express my heartfelt gratitude for your consistent delivery of exceptional content. Your knowledge is a beacon of light, and your insights continue to guide my digital marketing journey. James Jernigan’s YouTube channel has become a wellspring of inspiration for me, especially in the domain of web design. It’s there that I uncover new ideas and techniques that enrich my creative endeavors.

Hi, i think that i noticed you visited my weblog thus i came to “return the desireâ€.I’m attempting to to find things to enhance my website!I assume its good enough to use a few of your concepts!!

It’s really a nice and helpful piece of information. I’m satisfied that you simply shared this useful information with us. Please stay us up to date like this. Thanks for sharing.

cost of lasix 40 mg

Engaging and comprehensive! Encourages deeper exploration, much like Profitable Bots’ AI course.

First off I want to say fantastic blog! I had a quick question in which I’d like to ask if

you don’t mind. I was interested to find out how you center yourself and clear your head before writing.

I’ve had a hard time clearing my thoughts in getting my ideas out there.

I do take pleasure in writing but it just seems like the first 10 to 15 minutes

are wasted just trying to figure out how to begin.

Any suggestions or hints? Appreciate it!

I wonder what the competition in bartending scene has become and how competitive the bartending scene is in Dallas and Fort Worth.

I’ve always been interested in the earning potential for bartenders in this area.

How can bartenders in these cities comply with health and safety regulations?

I wonder how the rise of craft breweries is affecting bartending jobs in the area.

It’s fascinating to think about the role of bar managers in assisting bartenders.

You explained that wonderfully!expository essay writing https://topessayservicescloud.com/ professional writer services

best darknet markets tor markets how to access dark web

Excellent way of describing, and fastidious post

to get data on the topic of my presentation subject, which i am going to deliver in school.

смотреть онлайн

I appreciate the effort put into making this blog so inspiring. Great job!