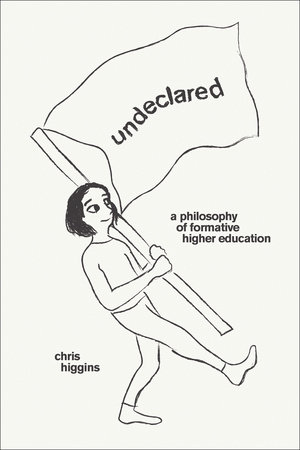

In a post sent in the 2023 Summer Newsletter entitled, “MIT Direct to Open” the Scholarly Communications team described the launch of a new initiative helping authors publish monographs and books open access. This year, Chris Higgins, the Department Chair of Formative Education in the Lynch School, published a book entitled Undeclared: A Philosophy of Formative Higher Education, which discusses the importance for practitioners to remain focused on the development of the whole person – particularly in how that relates to the value of disciplines in the humanities.

Because this book was published using MIT’s Direct to Open model, anyone with an internet connection has access to the full PDFs of each chapter. However, just because it is open access does not mean every version is free – the book is available for purchase if you would like to own the hard copy. Additionally, just because something is made open access does not mean the free version will be the most available – often times, hard copies of books are available to own, but also have an Open Access version. Googling, “Undeclared Chris Higgins” for instance, produces a number of results that link to copies of the book available for purchase, but it is not until the third result – the MIT Press site – where the book is available open access.

A good way to find open access materials is to begin your search in our Boston College Libraries search. While we may not have the particular eBook in our collection, querying the Boston College catalogue can yield results that will direct you to the open access version. If you are interested in checking out a hard copy free of charge, we do have a copy of the book available for check out at the O’Neill library.

Additionally, the Direct to Open page at MIT Press offers a complete, browsable list of open publications, and there is also a regularly updated spreadsheet of books that have been published open access via the model. As the beginning of July, 2024, there are over 4,000 titles that have been published open access.