Murals are not often thought of as a historical source, but scholars should consider murals as part of the historical record. These artworks have a long history. The idea of applying paint to a wall to communicate an idea or commemorate an event harkens back to the times of human cave dwelling. From ancient civilizations to the twenty-first century and in locations spread around the globe, decorated walls have been used to depict the ageless human need for self-expression. Murals have the ability to illustrate an artist’s vision of their environment, either how they saw their world or wished it to be seen. These artworks have a rich and detailed relationship with their creators, interwoven into human lives over hundreds of years, and yet contemporary audiences, both academic and non-academic, tend to overlook murals and their use as social tools. Sally Webster and Sylvia Rhor argue that this is because of the ubiquity of murals, that these artworks come with a paradox of being everywhere and nowhere, so commonplace in our society that we have forgotten their history and their usefulness. But these images have more to tell us.

Modern muralism was established in revolutionary Mexico at the beginning of the twentieth century. Previously, painted walls were used primarily for decorative purposes, but this changed as Mexican murals became political tools. Funded by the new revolutionary government, artists like Diego Rivera, used murals to educate and influence viewers on a host of revolutionary political and social topics. Mexican muralists established mural painting as a contemporary tool instead of simply an art form of the past. But mural painting changed after World War II. The emergence of the Cold War meant government funding to any non-conforming patriotic art was impossible. The depiction of labor struggles or issues regarding minority communities in any public place became almost unthinkable with the Cold War wave of cultural repression. Governments no longer commissioned public art that expressed aspirations of ‘ordinary people.’ Instead, many governments suppressed such art while the art world of museums and galleries deemed these artworks ‘unsophisticated.’

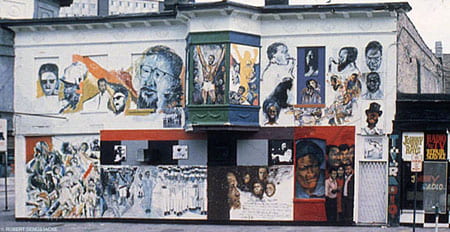

The use of murals as a political and social tool changed again in the 1960s with the first community mural in Chicago. Painted in 1967, the Wall of Respect was an outdoor mural painted by the Visual Arts Workshop of the Organization of Black American Culture. Composed of a montage of portraits of influential African American figures, the artwork is considered to be the first large-scale outdoor community mural and is credited with sparking the community mural movement across the globe. Painted by multiple Black artists, the Wall of Respect brought several new features to painted walls which would come to define community murals. The choice of location (outdoors in ‘neglected’ working-class and minority areas), artist initiative (groups of artists choosing to create projects instead of being hired by government bodies of professional administrators), the leading role of Black artists and artists from other oppressed groups traditionally excluded from the established art world (including women and people of color), and the involvement and support of the community (from financial sponsorship, practical support, discussion of the mural topic, inaugural celebrations upon completion, and people’s attachment and protection of murals). These new factors, especially the involvement of the local community, gave the Wall of Respect and murals which came after it a distinctive character and role.

This new type of mural became a tool for oppressed communities. In his article “A Wall Mural Belongs to Everybody,” John Weber stated that “most people today have no relationship to art. They do not go to galleries, or have money to buy art. They have no chance to develop; forms of self-expression and to say ‘this is me!’ Poor people, working people, Blacks, Latins, and other minorities are especially deprived of art and hungry for it. Almost nowhere in the mass media can they find an image of themselves which reflects with dignity their problems, struggles, hopes or rich heritage.” Mixing the influence of the radical 1960s battles for racial, gender, and sexual equality with the artistic desire for to venture outside the walls of the museum and engage with larger aspects of society, the innovative community mural modeled after the Wall of Respect provided an new form of expression to oppressed peoples. These murals were meant to reflect, engage, and belong to the community in which they were painted. The plaque hung above the Wall of Respect read: “We the people, of the community, claim this building in order to preserve what is ours.” These new community murals had no state blessing, but were instead spontaneous expressions of democratic will.

Inspired by the Black artists of Chicago, mural artists from the United States, through Europe, to Asia and Australia, developed systems of working with the local audience, depicting or engaging with issues that concerned the immediate community. Many of these artists sought to ‘change the world through art,’ by helping ordinary people rediscover their own creativity, and through it an ability to shape their future. By engaging with this neglected audience of the arts, or ‘ordinary people,’ community muralists strove to bring a form of visual representation to peoples who felt unseen, in both the imagery of the fine arts world and in the imagery of dominant power structures. Community muralists had no desire to be parachuted into a deprived area to create a work which displayed ‘cultured artwork’ to the under-educated masses; these communities already had their own culture, values, and traditions and community murals were meant to display these underrepresented images. When painting in predominantly working-class neighborhoods, often with large populations of oppressed groups, muralists immersed themselves in the communities they worked with. They engaged with the community from start to finish; choosing a theme, perfecting the design, applying the paint to the wall, and celebrating the finished project were all done with and for the community.

From the very beginning of the community mural movement, these artworks used public walls to assert community grievances against an establishment that deprived them of what was essential to their survival and self-respect. Painted walls became another form of public protest and demonstration. These communities usually lacked visibility in a public sphere dominated by traditional power structures, the same power structures often responsible for their community’s oppression. Murals became another means to combat this lack of visibility, a tool to demand that the issues of the community be seen and addressed. Communities around the globe have used political community murals: nationalist movements in Gaza, Northern Ireland, and the Basque Country, police abolition murals in Egypt and England, LGBTQ+ murals in Iraq, the United States, and Ireland, indigenous identity and resistance murals in Chile, Australia, and South Africa. The list goes on and on.

Community murals flourished through the 1970s and early 1980s, but with drastic cuts in public infrastructure and arts spending resulting from neoliberal policies, the production of community murals at a global level dramatically dropped in the 1990s. With this decrease in funding and conversations about community murals the historiography of these artworks became subsumed into a larger discussion about public art. Works regarding the use of murals in specific locations were printed throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, but the community mural movement as a whole no longer discussed. Moreover, as murals spread around the globe, these artworks became seen as commonplace, creating the background for everyday life. The radical history of these artworks has been lost with many passersby seeing a pretty picture instead of a tool of community activism. It is not as though community murals ceased to exist or became a less useful tool– there are still plenty of communities continuing to use murals –but rather that academics stopped discussing the history of these artworks.

Historians should pay more attention to this discounted community undertaking. Murals are tools which belong to the community and therefore should not be overlooked as a historical source. Developed in oppressed communities to instill pride, increase visibility, and claim belonging, these murals are not simply painted walls, but rather tools of activism. Murals establish a highly visible public space for overlooked communities to engage in issues of inequality and, as a result, combat traditional power structures. The imagery a community selected to surround itself with or imagery a community chooses to portray their identity to both themselves and the outside world can be crucial to aid to a historical understanding of these communities. These artworks are important in any community, but they are especially crucial in oppressed communities. Understanding the imagery largely and publicly painted on a neighborhood wall can be essential in creating a historical understanding of these communities and how they battled government oppression. Simply put, the history of modern murals should be known.

Works Cited

- Barnett, Alan. Community Murals: The People’s Art. Philadelphia: Art Alliance, 1984.

- Cockcroft, Eva and John Weber. Towards A People’s Art: The Contemporary Mural Movement. New York: E.P. Dutton and Co., Inc, 1977.

- Harris, Michael D. “Urban Totems: The Communal Spirit of Black Murals,” in Walls of Heritage, Walls of Pride: African American Murals, ed. James Priogff and Robin J. Dunitz. San Francisco: Pomegranate Communications, Inc., 2000.

- Miles, Malcom. Art For Public Places: Critical Essays. Southampton, UK: Winchester School of Art Press, 1989.

- Webber, John. “A Wall Mural Belongs to Everyone.” Youth 23, no. 9 (September 1972) 7-14.

- Webster, Sally and Sylvia Rohr. “Modern Mural Painting in the United States,” in A Companion to Public Art, ed. Cher Krause Knight and Harriet F. Senie. Malden, MA: Wiley Blackwell, 2016.

About the Author

Rachael Young (she/her) is a sixth-year Ph.D. Candidate in the Boston College History Department. Rachael’s dissertation examines community murals in 1980s Belfast and Brixton with a particular emphasis on the use of murals to combat the over-policing of the Irish Republican and Black communities. You can find her on Twitter @RAYHistoryNerd.

To stay up to date on all things Annotations & Abstracts, follow us on Twitter @bchistcommons.