As Ireland celebrates the Decade of Centenaries, ten years of events commemorating the Irish Revolution, some commentators have noted a curious phenomena in the representation of women. Despite the increased attention to women’s involvement in the revolution, the women remembered were considered “exceptional” or as existing apart from revolutionary men. The noted scholar Oona Frawley described this “oblivious remembering” as a form of remembrance that lacks awareness of the systemic biases in official approaches to the past. In order to understand why some revolutionary women are remembered while others are forgotten, historians need to interrogate the structural forces that influence the construction on personal and public memory. This examination of the records left by Mary Flannery Woods, a writer turned revolutionary, augments current understandings of women’s participation through an analysis of the highly gendered personal narrative that she produced in the decades after the revolution. Before the revolution Woods was a notable writer with serialized stories and poems published in Irish newspapers and periodicals. After the Easter Rising, she joined the women’s paramilitary organization Cumann na mBan and was deeply involved with both the Irish Volunteer Force and the Irish Republican Army. Not only did she open her home to harbor republican paramilitaries and stolen rifles and ammunition but she was known to smuggle weapons and funds herself.

Wood’s archival records indicate that women’s participation in the revolution transgressed traditional notions of femininity as well as the ways in which gendered political discourses influenced and obscured women’s stories. For decades, republicanism and masculinity were deeply intertwined in the Irish consciousness. Consequently, this obscures the contributions of revolutionary women as well as the solidarity between men and women during the struggle for independence. Moreover, gender influences the construction of women’s narratives in powerful ways. Woods and other revolutionary women de-emphasized their personal experiences, indicating an internalized belief that their stories were less worthy of retelling while simultaneously emphasizing men’s contributions to the revolution and devoted significant space to retellings of men’s stories. In particular, they sought to preserve the memory of martyred republican men.

As a clandestine revolutionary, Mary Flannery Woods does not appear in the historical record often. Considering the danger of keeping written records of revolutionary activities during a time when raids by the opposition were unavoidable, there are few documents from the period of 1916-1923 in Woods’ archival record. However, in 1951, Woods gave an extensive witness statement as part of Ireland’s Bureau of Military History oral history project. This research also relied on the Molly Flannery Woods Papers archived at Boston College’s John J. Burns Library. Her personal collection includes her military pension application, correspondence, and scrapbooks of her written publications and newspaper clippings. It is through this collection of sources that Woods’ personal narrative emerges from the historical record.

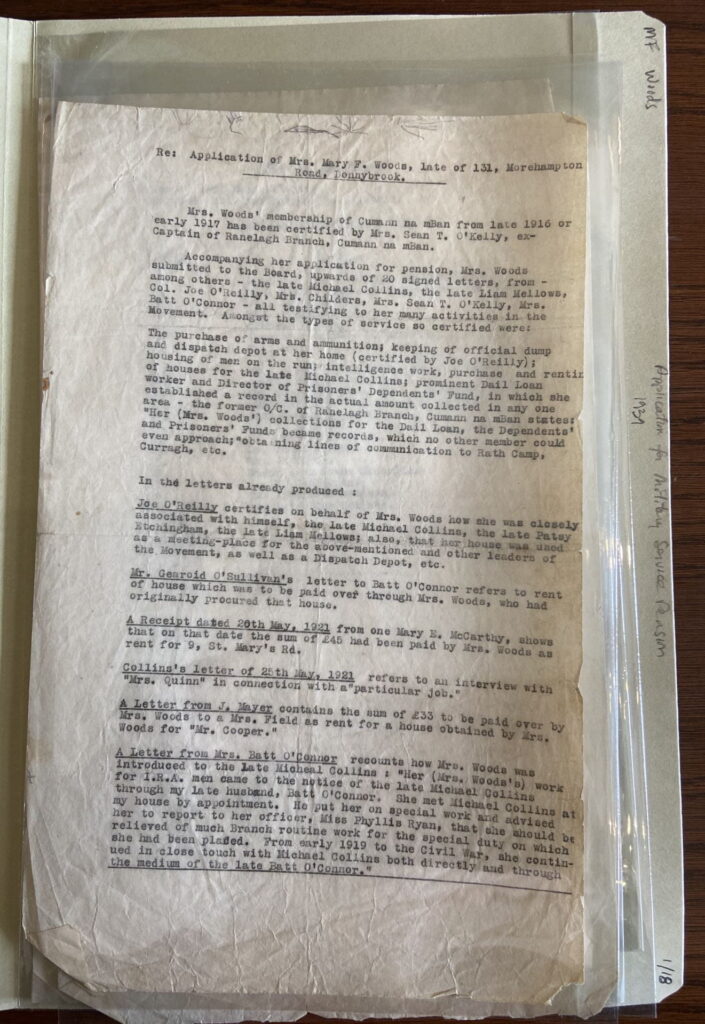

In her witness statement, Wood detailed her impressive range of revolutionary activities, including directing the Prisoner’s Dependents Fund and establishing new branches of Cumann na mBan. Her home at 131 Morehampton Road in Dublin was a refuge for many during both the War for Independence and the subsequent Civil War. She worked closely with the Irish Volunteers, the nationalist paramilitary group, many of whom passed through her home for food, clothes, and a safe place to sleep, often placing the safety of herself and her family on the line. As such, Michael Collins, a member of the first Dáil Éireann, general for the Irish Volunteers, and Director of Intelligence for the IRA, took note of Woods. Although she remained a member of Cumann na mBan, in 1920 Collins instructed her to “absent myself from them and to act as if I were getting cool and careless.” This allowed her to maintain a low profile so that she could procure safehouses, conduct espionage, and collect financial and material resources without raising suspicion. She was bold enough to purchase guns from the British Army or the Free State Army that she would resell to the IRA without ever being arrested for treasonous activities.

In this instance, distancing herself from the women’s organization allowed her to be more effective in her role as a woman revolutionary. In a letter of reference for Woods’ military pension application, Phyllis Ryan, Wood’s Cumann na mBan branch commander, recalled that “after a certain period [she] no longer carried out the routine work of the Branch as [her] services became more valuable to the men by absenting yourself ordinary duties.” Woods never rose in the ranks of Cumann na mBan, which might have garnered her a prominent place in the history of the organization, but that would have proven disadvantageous to her work. Furthermore, Ryan’s assessment of Woods’ contribution to the revolution indicated that the value of women’s work was measured by how useful it was to the men.

While Woods’ witness statement covered her personal experiences and active roles she played in the revolution, a significant portion of her testimony focused on the republican men. She went to great lengths detailing what the men she harbored at her house did and said while on the run, especially when she overheard their military or intelligence plans. It is important to note that the witness statements for the Bureau of Military History were collected by army officers, most of whom were men. Woods might have thought that the officers would be more interested in her memories of these men rather than of herself or other women. She might have even been prompted by the officers to focus on those stories. However, although this context is important for interpreting her witness statement, it is as likely that to some degree the narrative of the revolution Woods constructed for herself reflected these values and was highly gendered in specific ways.

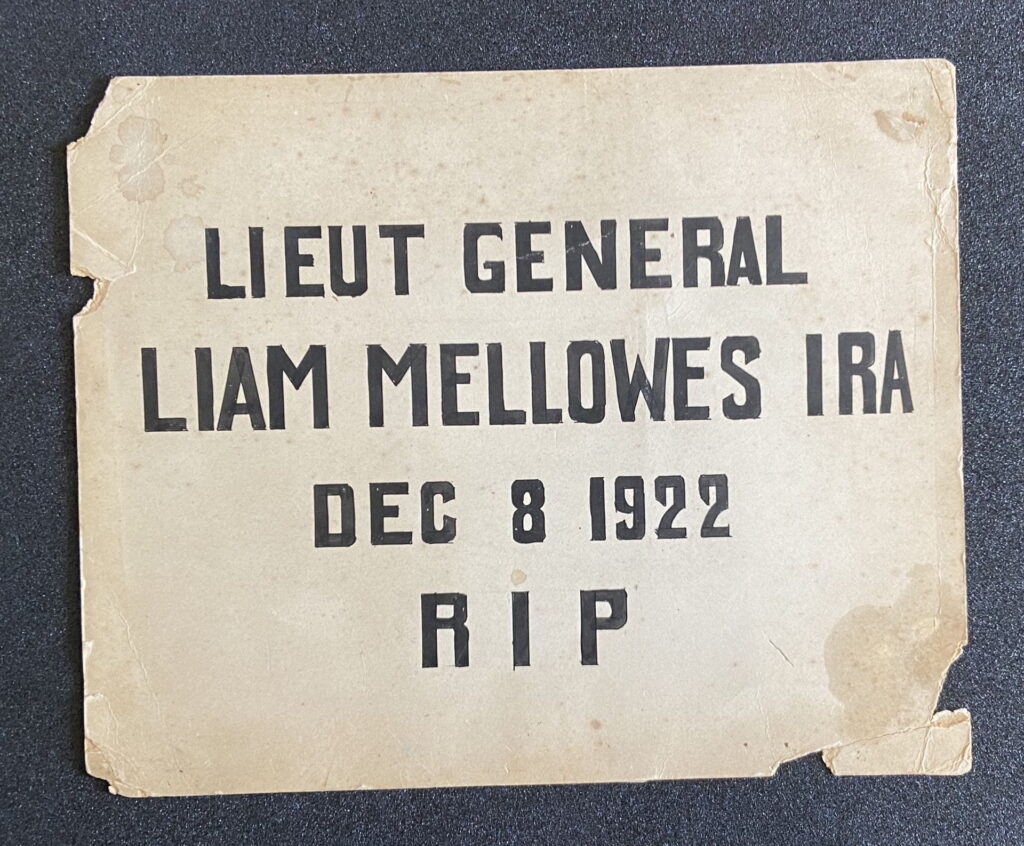

During the revolution, Woods provided refuge for Liam Mellows, the Sinn Féin politician and senior member of the IRA, who spent most days on the run, particularly as a leader of the anti-treaty IRA during the Civil War. Because of his stance against the treaty, Mellows was imprisoned upon his surrender after the Battle of Dublin and executed by the Free State in 1922 as a reprisal. Woods, considering him to be like family, dedicated herself to ensuring that Mellows was remembered among the ranks of the republican heroes. A disproportionate number of pages of her witness statement covered Mellows’ role in the Volunteers and IRA, relationships with other republican men, time in prison and on the run, and his political ideology. Her own archives contain part of her collection of materials related to Mellows. Amongst her own materials is a placard reading “Lieut. Liam Mellows IRA” that was placed upon his coffin at his funeral, and which she preserved for decades. Her three scrapbooks filled with news cuttings of her literary publications and columns about the republican movement also contain numerous articles about Mellows, particularly those memorializing him after his death. Woods also donated several of his items to the National Museum of Ireland including his gun holster, a poignant symbol of republican masculinity, and the notebook he used to record purchases of guns and ammunition for the IRA. Woods annotated the notebook herself, as she was familiar with Mellows’ style of record keeping, ensuring that future generations would understand the importance of the artifact.

Pasted alongside her stories and poems in her scrapbooks is a piece Woods wrote titled “The Gladiator.” Published in 1921, the article appeared in Young Ireland long before Mellows’ death, but nevertheless articulated her respect and admiration for the republican leader. Woods confirmed that the unnamed gladiator was Liam Mellows both in her witness statement and an annotation in her scrapbook. The story’s narrator implored the gladiator to “‘share your story with the world… You owe it to Ireland and to yourself.’” Already Woods felt strongly that Mellows’ story fit into the larger narrative of republican heroes. If anything, his death at the hands of the Free State only solidified this and made him a martyr.

When women recount their memories of the revolution yet focus on martyred men is it because their own contributions are viewed as less important by society then and now? Do they discount their contributions? Is it because they think their best contribution to historical memory is to preserve the stories of these men? The construction of memory is a complicated and oftentimes unconscious process and socially accepted conceptions of gender proved highly influential in the formation of Wood’s personal narrative. Thus, deconstructing the social and cultural mechanisms that conceal women’s histories is a crucial step forward in expanding the scholarship on women’s participation in the Irish revolution.

Works Cited

- Ferriter, Diarmaid. A Nation and Not a Rabble: The Irish Revolution, 1913-1923. New York, NY: The Overlook Press, 2015.

- Frawley, Oona. Women and the Decade of Commemorations. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2021.

- McDiarmid, Lucy. At Home in the Revolution: What Women Said and Did in 1916. Dublin: Royal Irish Academy, 2015.

- Ward, Margaret. Unmanageable Revolutionaries: Women and Irish Nationalism. London ; East Haven, CT: Pluto Press, 1995.

About the Author

Tiffany Thompson (she/her) is a second year doctoral student in the History Department at Boston College. Her research interests include women and gender, migrations and diasporas, and civil rights and the Troubles in Northern Ireland. She is beginning work on her dissertation which will examine gender, violence, and the dislocation and migration of urban families during the first decade of the Troubles. Find Tiffany on Twitter @tiff__thompson.

To stay up to date on all things Annotations & Abstracts, follow us on Twitter @bchistcommons.

Undeniably consider that which you stated. Your favorite justification appearedto be on the web the easiest thing to bear in mind of. I say to you, I definitely get irked whilst other folksconsider concerns that they just do not know about. You controlledto hit the nail upon the top and defined out the whole thingwithout having side-effects , folks could takea signal. Will likely be back to get more. Thanks

Thankfulness to my father who stated to me on the topic of this blog, this web site is actually amazing.

Hi there! This blog post could not be written any better! Going through this article reminds me of my previous roommate! He always kept preaching about this. I most certainly will forward this article to him. Fairly certain he’ll have a very good read. Many thanks for sharing!Feel free to visit my page … https://ketodeluxegummies.com