5.25

[1] Psȳchē vērō humī prōstrāta et, quantum vīsū poterat, volātūs marītī prōspiciēns extrēmīs afflīgēbat lāmentātiōnibus animum. Sed ubi rēmigiō plūmae raptum marītum prōcēritās spatiī fēcerat aliēnum, per proximī flūminis marginem praecipitem sēsē dedit. Sed mītis fluvius in honōrem deī scīlicet [2] quī et ipsās aquās ūrere cōnsuēvit metuēns sibi cōnfestim eam innoxiō volūmine super rīpam flōrentem herbīs exposuit. [3] Tunc forte Pan deus rūsticus iūxtā supercilium amnis sedēbat complexus Ēchō montānam deam eamque vōculās omnimodās ēdocēns recinere; proximē rīpam vagō pāstū lascīviunt comam fluviī tondentēs capellae. Hircuōsus deus sauciam Psȳchēn atque dēfectam, [4] utcumque cāsūs eius nōn īnscius, clēmenter ad sē vocātam sīc permulcet verbīs lēnientibus: [5] “Puella scītula, sum quidem rūsticānus et ūpiliō sed senectūtis prōlixae beneficiō multīs experīmentīs īnstrūctus. Vērum sī rēctē coniectō, quod profectō prūdentēs virī dīvīnātiōnem autumant, ab istō titubante et saepius vaccillante vestīgiō dēque nimiō pallōre corporis et assiduō suspīritū immō et ipsīs marcentibus oculīs tuīs amōre nimiō labōrās. [6] Ergō mihi auscultā nec tē rūrsus praecipitiō vel ūllō mortis accersītae genere perimās. Lūctum dēsine et pōne maerōrem precibusque potius Cupīdinem deōrum maximum percole et utpote adolēscentem dēlicātum luxuriōsumque blandīs obsequiīs prōmerēre.”

Distraught by Cupid’s departure, Psyche attempts suicide, but is saved.

quantum vīsū poterat: “as far as she was able to see.” Visū = supine expressing purpose (A&G §510).

rēmigiō plūmae: “by the oarage of his wings;” this famous phrase is imitated from Aeschylus (Ag. 52) via Vergil.

fēcerat aliēnum: “had taken him from her” (Kenney). Aliēnum emphasizes Cupid’s distance from Psyche.

in honōrem deī scīlicet: Scīlicet (“I guess, apparently”) indicates that this is intended to be read unseriously. We understand that even natural forces fear Cupid’s powers, and must avoid angering him.

volūmine: this word is being used in a less-common sense, to refer to an eddy or current.

Pan & Ēchō: See Media for this story.

proximē: here used as a preposition + acc.

capellae: the she-goats are the subject of the phrase

sauciam: see 5.23.4

25.5: Pan’s divinity allows him to foresee Psyche’s condition, so it is deeply ironic that he pretends to not be using his powers, but instead using the wisdom of old age and diagnosing her psychological issue from her appearance.

accersītae: from arcessō, -ire, “to summon;” genitive modifying mortis.

pōne…precibusque potius…promērēre: The alliteration emphasizes Pan’s message: she must re-earn Cupid’s favor after dishonoring him.

prōcēritas, -ātis f.: height, length, distance

supercilium, -ī, n: peak, ridge, summit

recinēo, -ere: to repeat, echo, recall

pāstus, – ūs, m.: see 5.17.4

lascīviō, -īre: see 5.22.6

capella, -ae, f.: she-goat

hircuōsus, -a, -um: goatish

utcumque: in any way, however

scītulus, -a, -um: handsome, pretty

ōpilio/ūpilio, -ōnis, m. [for ovilio, from ovis]: shepherd

prōlixus, -a, -um: stretched far out, long, broad

coniectō, -āre: to guess, conclude

autumo, -āre: to affirm, assert, think

titubo, -āre: to stagger, totter, reel

vacillo, -āre: to sway to and fro, stagger, totter, waver

suspīritus, -ūs, m.: a deep breath, a sigh

marceo, -ēre: to droop

praecipitium, -ī, n.: a fall, falling headlong

utpote: see 5.18.4

percolo, -āre: revere, worship

dēlicātus, -a, -um: pleasing, charming

obsequīum, -ī: see 5.18.1

prōmereor, -ī : win over

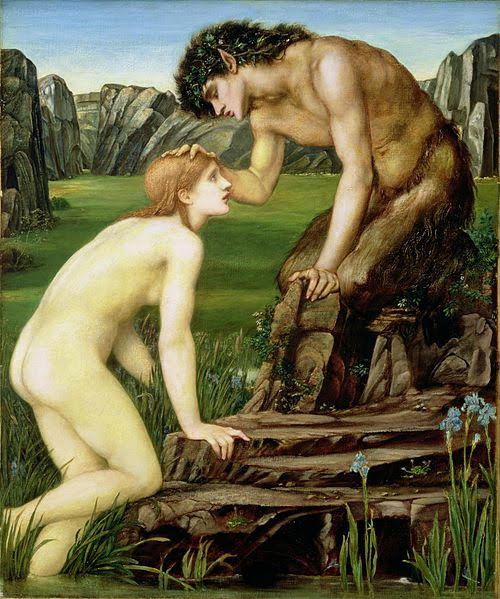

Above: Edward Burne-Jones, “Pan and Psyche”, 1872-74, oil on canvas, Burne-Jones Catalogue.

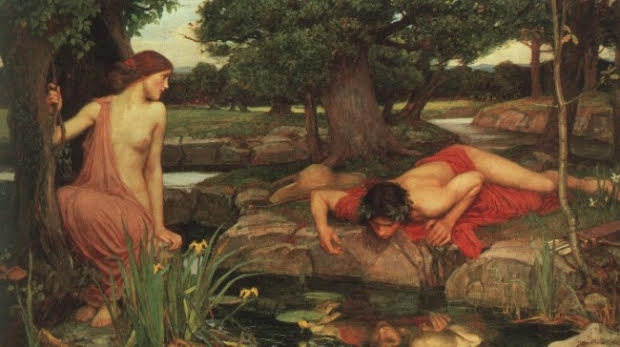

Pan & Echo: Starting in the Hellenistic period, Echo was personified as a nymph who can only repeat back the last word she hears. In the most famous Latin version of her story (Ovid, Met. 3.359-510), Echo is helplessly in love with Narcissus; Pan does not appear. Below: John Willaim Waterhouse, “Echo and Narcissus,” 1903, Oil on canvas, Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool. Photo credit: GalleryIntell.

But Greek versions focus on Pan’s (usually unsuccessful) love for Echo (e.g. Moschus fr. 2). The fullest extant version is in Longus’ novel Daphnis & Chloe (3.23, trans. Jeffrey Henderson Loeb 2009); it is much darker than the cozy scene Apuleius evokes: “[Echo] was brought up by Nymphs and taught by Muses to play the syrinx and the pipes, tunes for the lyre, tunes for the cithara, every kind of song. So when she reached the flower of maidenhood she danced with the Nymphs, she sang with the Muses. She shunned all males, humans and gods alike, liking her maidenhood. Pan grew angry with the girl, being jealous of her music and unsuccessful at winning her beauty. He afflicted the shepherds and goatherds with madness, and they tore her apart like dogs or wolves and scattered her limbs, still singing, over all the earth. As a favor to Nymphs, Earth hid all her limbs and preserved their music, and by will of the Muses, she has a voice and imitates everything just as that girl once did: gods, humans, instruments, animals. She even imitates Pan himself as he plays the syrinx, and when he hears her he jumps up and chases over the hills, yearning only to know who his invisible pupil is.”