Pilgrimage Course

My attraction to Fisterra was primal. I knew from pictures that it was beautiful, yes. But what drew me there was the gravity of what I would call spiritual sedimentation. Prior to the emergence and coalescing of the cult of St. James, the site had apparently been a site of Pagan worship. In much the same way that the great basilicas of Europe were repurposings of Roman imperial courts, Fisterra was a kind of spiritual palimpsest, a natural place for wonder and worship, a site of great natural beauty that different cultures had consecrated.

This alignment of the natural and the cultural, or the physical and the spiritual, was manifested in the photo I took of the stone cross cutting across the sea and sky. As though it is holding the sky up and binding the horizon together. It cut through the bells and whistles of Camino commoditization that saturated Santiago, the shops hawking the swag of St. James. It cut through the heavy crust of history that separates us from the elemental encounter with the origin, the “founding moment.” And it confirmed a suspicion I had had all along before and during my own Camino journey: that our attachment to the pure origin and foundation, the projections we make about saints and heroes and founders, the fascination with relics—that all of these things threaten to blind us to the true spirit of pilgrimage.

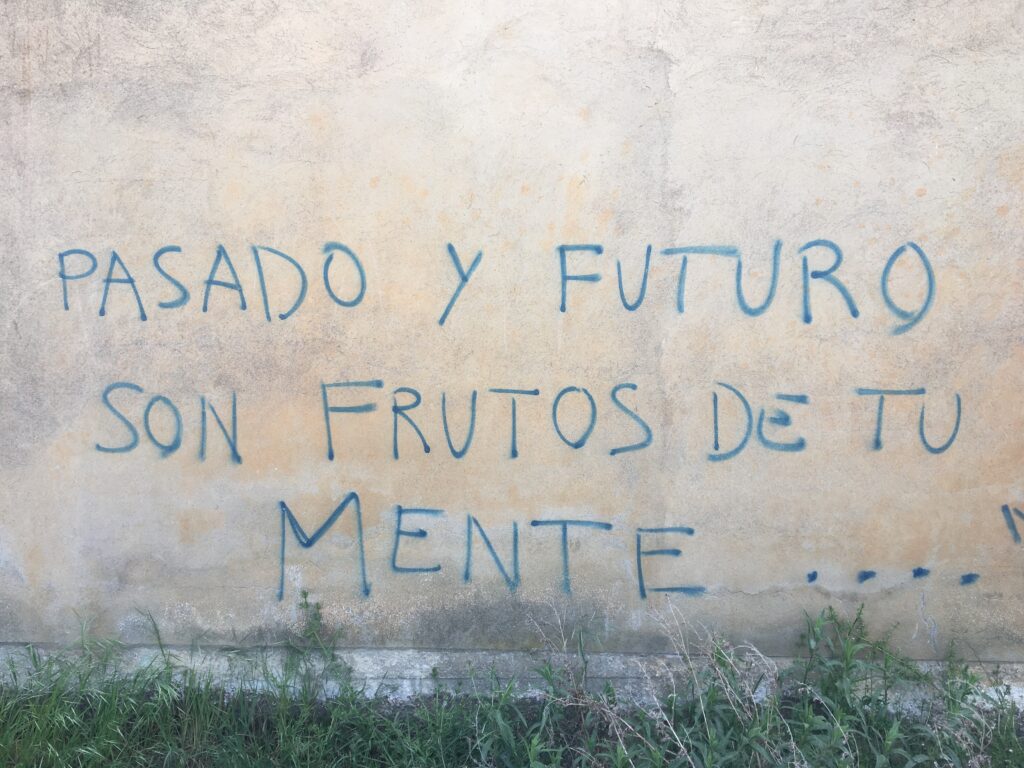

There was a message graffitied on a wall we passed on the outskirts of one of the towns several days before: “Past and future are fruits of the mind.” The greatest distance is the distance to here. The paradox is that we must move out of stillness to find stillness. In this way, the Camino is like a good Zen koan. You have to sit and walk and struggle with it, step by step, blister by blister, to figure out why you are walking, until your mind at last yields to what is, what has always been there underneath your feet.